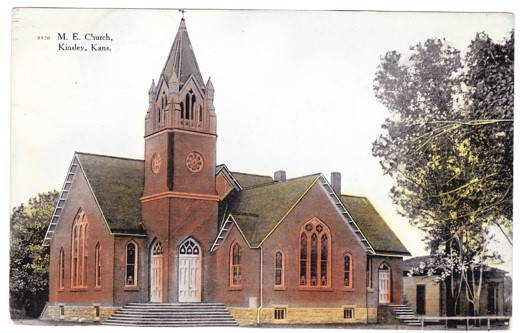

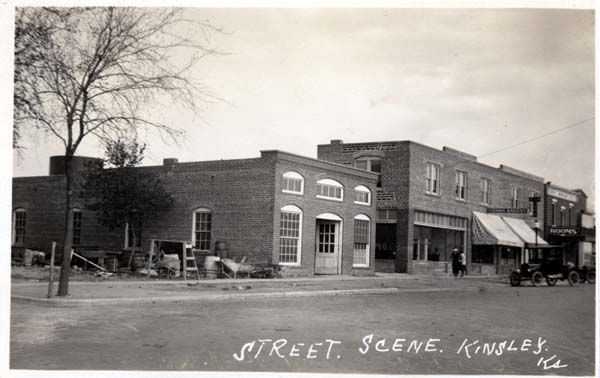

When looking for a topic for this week’s article, I went to the Kinsley newspapers of 100 years ago to see what was happening. Using www.newspapes.com, which is available to all Kansas residents through the Kansas State Historical Society website, I found that in the spring of 1923 a business area on 600 Colony Ave was being redeveloped and would be called the Oiphant block.

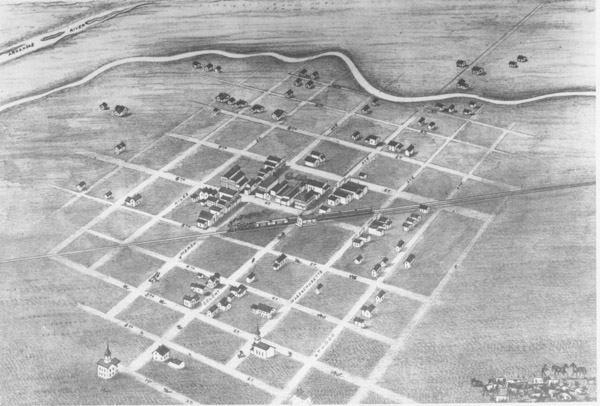

The editor of the Kinsley Mercury described this west side of Colony, which extends north of the high school to the railroad tracks, as having old dilapidated frame buildings that “had stood there for more than a third of a century offering neither commodity or beauty.”

One exception existed. In 1913 Roy Hatfield had built a brick carpentry shop, north across the ally from the high school. This building no longer exists and is an empty lot. According to the 1920 Sanborn Insurance map, going north from Hatfield’s, there were frame buildings housing an electric supply business, an auto radiator repair shop, the Midland Hotel, a carpentry/paint shop, a restaurant and finally ending with a threshing machine warehouse angling next to the railroad tracks.

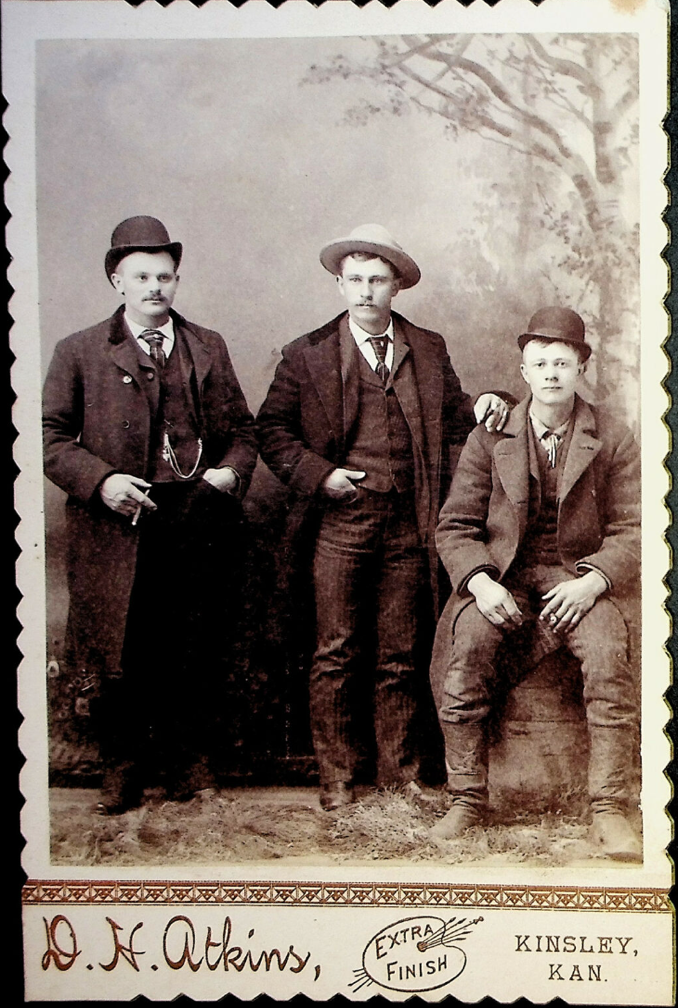

The August 31, 1922 issue of the Kinsley Graphic reported that H. B. Oliphant (Hugh Bartes Oliphant, 1854-1933) and his sons, Hugh, Jr. (1884-1959) and N. D. Oliphant (Norman Dix, 1885-1847) purchased land on the north side of Hatfield’s. H. B. had built many homes in Kinsley and he was looking to improving the city’s look and future.

The Oliphant brothers wanted to house their Kinsley Ice Cream and bottling works in their own building. They constructed the brick buildings which still stand at 626 and 624 S. Colony Ave. The creamery was housed in the south building and consisted of an office in front (17’ X 22’) with the creamery, ice cream factory and bottlings works in the rear (22’ X 90’). The office work was done by Mrs. N. D. Oliphant (Clara) and daughters Ethelyn (KHS 1924) and Velma (KHS 1924).

Norm Oliphant was the general manager and in charge of the creamery which was managed by Luther McAdoo, who was described as ”one of the best butter makers in the game.” The plant’s modern equipment could produce 1000 lbs. of butter a day. The surrounding towns and every grocery store in Kinsley carried the famous Blue Ribbon brand of butter manufactured by Norm and Hugh Oliphant.

The foreman of the ice cream business was Don Kerr. Sufficient sweet cream and milk had to be secured for the large business. The editor wrote the following description of the plant:

“Two brine freezers are employed in manufacturing the ice cream which turn out 100 gallons per hour. When the ice cream began going into the packers, it didn’t take but a moment to see it was but a twinkling until ten gallons of ice cream was ready to be placed in the hardening room.”

The brine freezers mentioned above worked on the same principle as the old home ice cream makers with salt brine used to lower the temperature. More than four train cars of crushed rock salt (perhaps from Hutchinson?) were necessary to pack out the ice cream each year.

The shipping room in the back was arranged so that a large truck could be loaded within the building. The shipping floor was the same height as the bed of the truck to minimize lifting.

The second story of the building was used for storing cartons, syrups, and other supplies.

Hugh Oliphant was in charge of the bottling works part of the business where the ingredients for pop, near beers and ginger ale were mixed, bottled and distributed. “Near beer” is what we call three-two beer (3.2 % alcohol by weight or 4% by volume). Near beer was a mild beer compared to the beer before WWI which was strong even by today’s standards.

During Prohibition, 1920-1933, the sale of beer was banned, but not the ingredients for making it. Malt syrup was advertised and sold as a baking ingredient, but it was used to make beer. Near beers with their lower alcohol content could be produced and sold legally during Prohibition.

The bottling works department was quite a large business itself. It took almost 2000 cases to keep this department in operation throughout the season and shipments were “made on almost every train leaving Kinsley daily.”

(To be continued next week as we progress north up the block.)