Eighty-five years ago on April 14, 1935 it was Palm Sunday, and the plains were experiencing a different kind of disaster. Commonly known as Black Sunday, it was the day one of the worst dust storms in American history rolled through. It is estimated to have blown 300 million tons of topsoil across the country, some of it ending up in Washington, D.C. It caused immense economic and agricultural damage.

Over 30 of the 85 oral histories the library has recorded contain memories of Black Sunday and the many other dust storms of the Dirty Thirties. The following excerpts come from a few of the transcripts which are all accessible on the library website for you to read. Perhaps they will inspire you to preserve your life story. This “stay home” time provides the perfect opportunity to to do it. Just think about it. All of our life stories will now include how we survived the “Great Pandemic of 2020”.

Catherine Hattrup (1925-2020) told of her fear on Black Sunday. “I was nine years old, and I was at my Grandmother Gleason’s house. . . her house was a big two-story, and it had a wrap-around porch. She went out on the porch, I don’t know whether she’d been listening to the radio or what, but she came back in and she said, ‘Oh my, there’s a horrible black cloud. I don’t know what it is, but it’s coming this way. We must close up all the windows and doors and we must pray’. . . .I was afraid that it was the end of the world. I was scared, and we prayed, and I do remember that it got so dark that she had to turn the lights on…. I think it was somewhere between four and five o’clock . . . .I just remember that we had to have the lights on. Then I remember my Dad saying, ‘The chickens think it’s night, because they went to roost.’ “

Jeff Mead was a very small boy on Black Sunday but he still remembers the storm. “That particular day, my Aunt Joan hadn’t graduated from Centerview yet, so she was in a quartet. This was Palm Sunday, so the quartet was to meet at the Methodist Church in Centerview that afternoon and practice Easter music. And so I went with Grandpa, and we had an old rickety building out there where he kept the car. We got the car out, and as we came around to park in front of the house here, so my aunt could take the car and go practice music, and there, I wish I knew how tall those clouds were. That rolling dust. It was coming toward us. Grandpa told me, ‘You get in the house, and I’ll go put the car away.’ And it hit before he got back to the house. In this house, at 3:00 in the afternoon, of course, there wasn’t any insulation in the house. When they built in those days, there was a wall, and it was all lath and plaster, that was the only insulation. But in this house, right here where we are sitting, I would not have been able to see your face (three feet away). . . .Like I say, I wasn’t quite five years old, but it comes to me, ‘Is this the end of the world?’ It looked it.”

Robert Stach (1925-2011) recalls being out when the storm came in. “I do remember the dusty days and stuff before we moved to town, and then after we were in town, because I remember what they called Dirty Sunday in 1935. Mother had my brother and my older sister then, and we had walked across town to the Ford Station corner there in Kinsley and we lived over on the north side park, . . . Mother went over there to visit some friends of the family that were in the south end of Kinsley. I remember pushing a bicycle back because there was too much wind and stuff for her. We couldn’t stand up. Mother was carrying my older sister who was a very small little baby.”

Earl McBride (1915-2011) and his father saw the impending storm coming. “One of the things that I remember about it was Dad and I were working on the windmill one day. We could see what looked like a black cloud coming from the north. He said, ‘We probably better get down off here; that thing is going to hit here pretty soon.’ We got down off the tower. When it hit, it just turned the afternoon into darkness. I never will forget the chickens. They were running to get to the chicken house and go to roost because they thought it was night.”

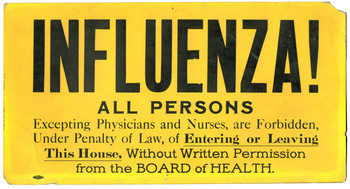

Buford Brodbeck 1925-2014 remembers the disease that the dust brought on. “I can remember the dust storms worse than anything….When they’d roll in, it would just get dark. I had a cousin that lived out in Manter, Kansas. She got dust pneumonia real bad and my dad and mother went out and got her and brought her back here to live for a while. I thought, holy hell, it’s worse out there than here! When you got hit, you just got in the house and tried to keep from choking to death. You’d put sheets up in the windows to try to keep it out. Wet them a little, and the next day they’d be just as black as you could see….”

More Dust Bowl stories can be found in the oral histories of Norma Gatterman, Virginia Rapp, Jean Titus, John J. Riisoe, Carman Rodriguez, Jim Mowry and many others. You can read their transcripts, listen to theri complete audio, or watch a short video on the library website. Check out the Oral History index in the left menu. And remember, today is a good day to start writing your history or begin a pandemic journal for yourself or your child.