One of my favorite childhood memories is of coyotes yipping and howling in the distance as I fished on summer evenings in Michigan. Today, I still like to listen to their night songs on my hill.

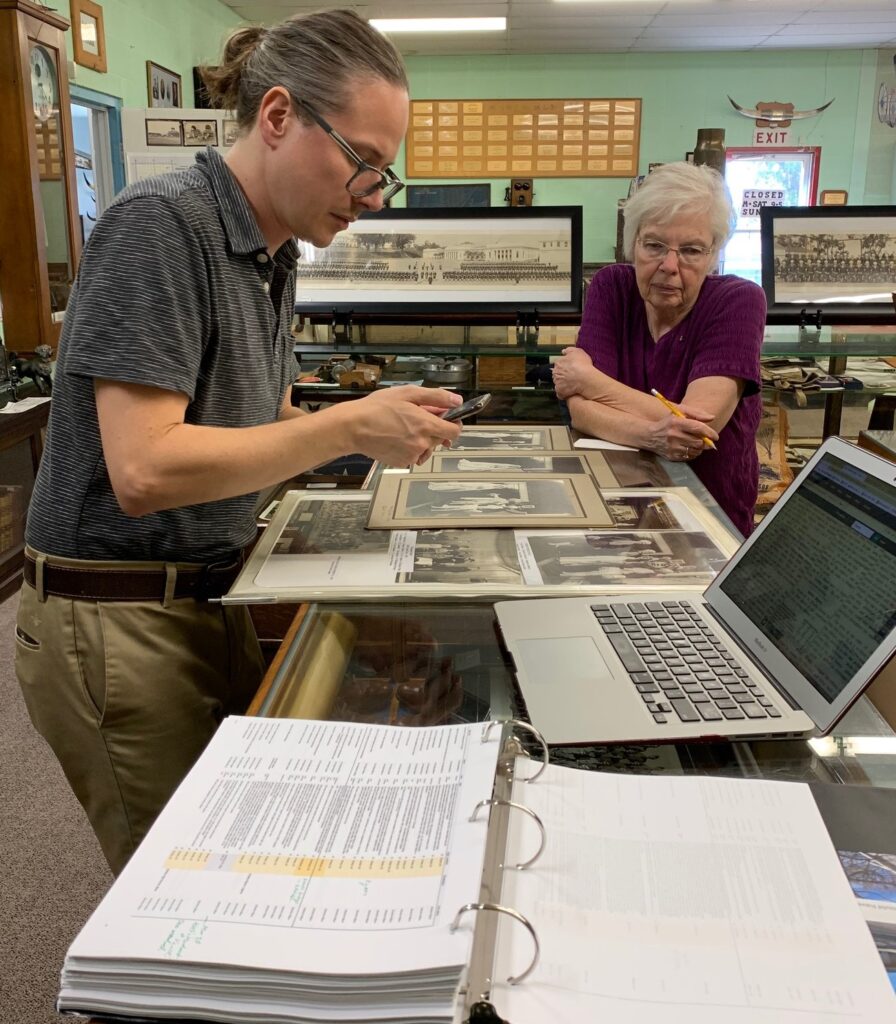

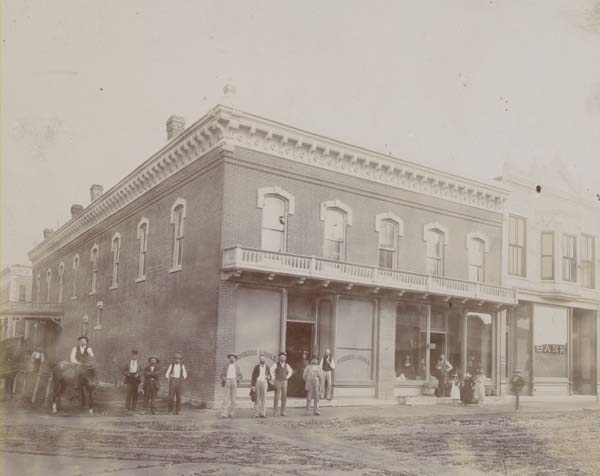

D. J. Martin, formerly of Lewis, gave the library this picture of a group of men after a coyote hunt in Garden City on July 4, 1911. It aroused my curiosity about coyote hunting.

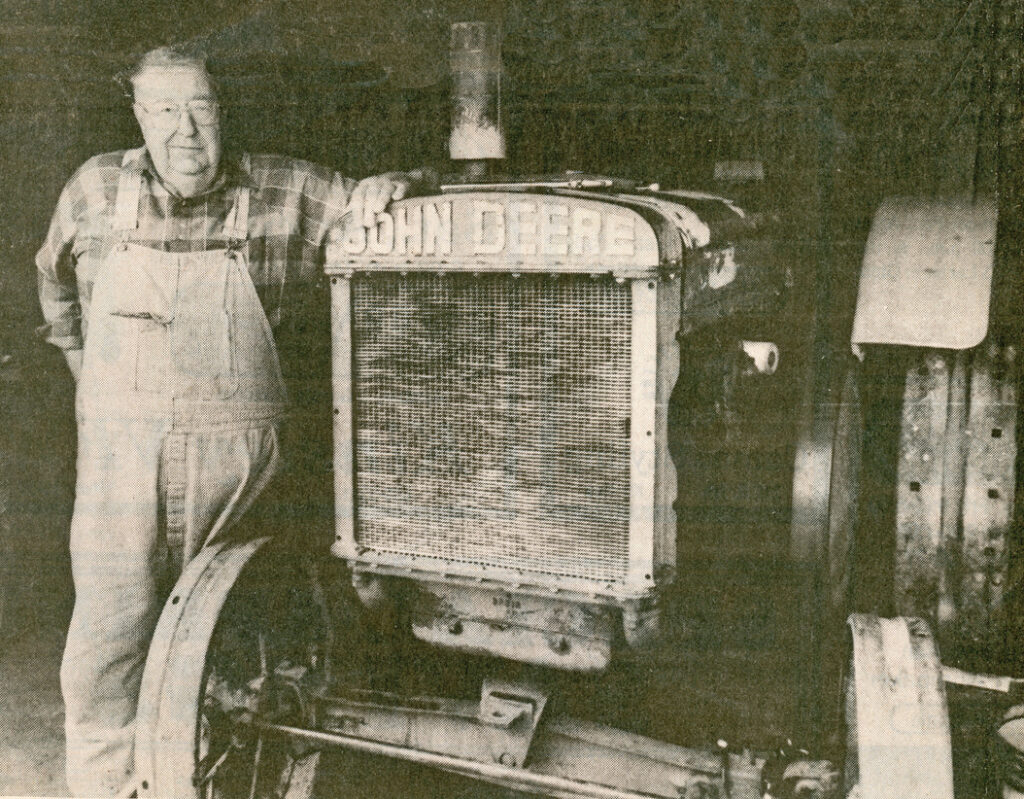

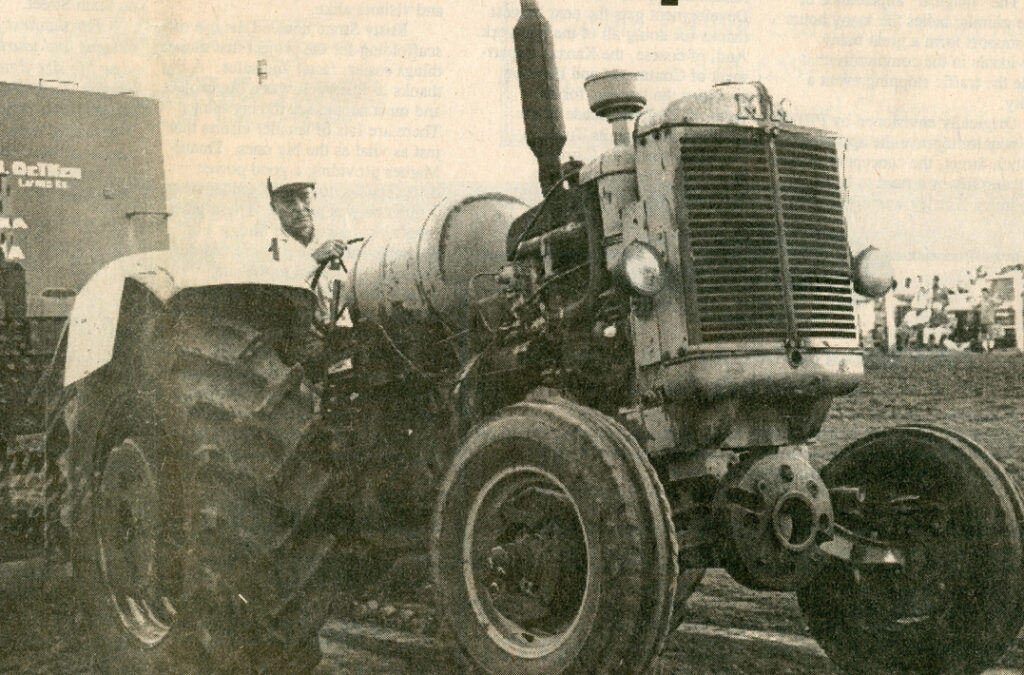

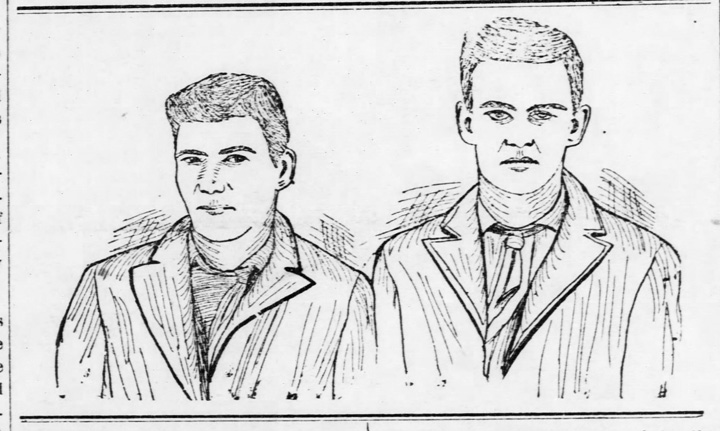

Picture of John Miller (1878-1957) in the driver’s seat. He was Darrel Miller’s great uncle and had a car dealership in Garden City. William Lohman (1870-1934) standing, Donald J. Martin (1907-1996) seated on the hood with two of Miller’s mechanics at the rear.

Over the years, people have either loved or hated the prairie “wolf”. To the Crow tribe, Old Man Coyote was the supreme creator of the earth and all living animals. The Nez Perce believed that humans sprang from Coyote’s blood. Tribes in the southwest thought the coyote was the Creator’s dog, and other tribes portrayed him as a cunning trickster.

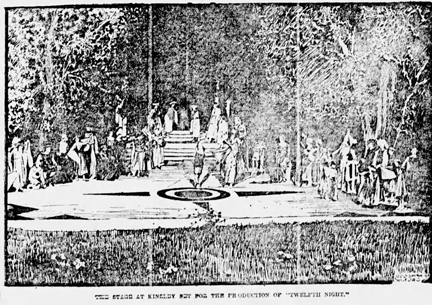

Kinsley High School athletes look to the coyote mascot to imbue them with its attributes of adaptability, cunningness, patience, relentless persistence, speed, invincibility, and a reliance on a pack for success.

But when the first farmers and ranchers arrived here 150 years ago, they fought the coyote as a hated enemy to be eradicated. Coyotes raided their chicken houses and turkey pens and killed sheep and calves.

In 1872, just two years before Edwards County was formed, Mark Twain described the coyote in his book, Roughing It.

“The coyote of the farther deserts is a long slim, sick and sorry looking skeleton with a gray wolf skin stretched over it, a tolerably bushy tail that forever sags down with a despairing expression of forsakenness and misery, a furtive and evil eye, and a long sharp face, with slightly lifted lip and exposed teeth.”

In 1882, the county commissioners first passed a resolution offering a bounty for killing wolves, coyotes and wild cats. People were to bring in the scalps with both ears to receive a $1 bounty.

Early on, coyote hunts were organized to both eliminate the predator and to provide for a social gathering. Citizens would band together for “circle hunts” like ones used to flush out and kill rabbits. These hunts were held on horseback with dogs. Firearms were not always allowed.

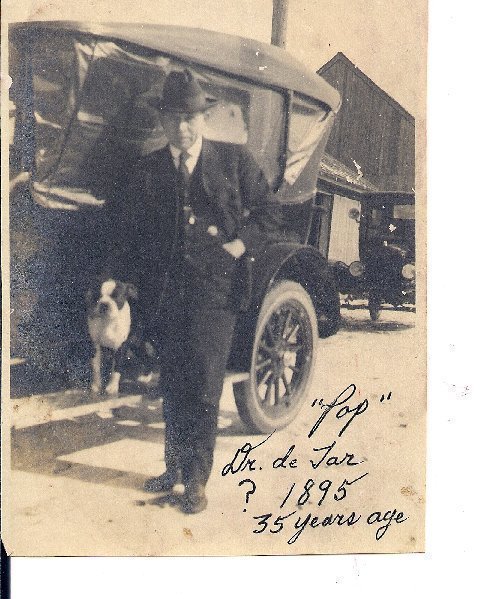

The Dec. 22, 1893 issue of the Kinsley Graphic described a coyote drive that captured “three coyotes, the dogs killed two and M. DeTar and C. L. Fuiton shot the other two.”

The next week, the largest coyote drive of that season was held. The lines of hunters were organized as follows: “East, Lewis; South, south line of sand hills; North, Jonas Miller’s farm; West, Offerle with the drive ending 3 miles east of Kinsley.

The bounty on coyotes was removed in Edwards County in 1894 but reinstated in 1899. In July of that year, the county paid out “over $600 in bounties for coyote scalps at $1.00 per head. “This is at the rate of 2,400 coyotes a year, killed in this county. Possibly these coyotes were all killed in Edwards county but we doubt it. Past experience has shown that it is not profitable to offer bounty for coyote scalps unless the neighboring counties do the same. The opportunity for fraud and the temptation is too strong. It is altogether improbable that 2400 coyotes a year can be killed in as small a county as this.” (Graphic, July 28, 1899)

The old newspapers report many coyote hunting stories. Out where I live in the spring of 1911, A. G. Eggleston (1860-1927) and John Denton killed 11 coyotes, and Nathan Cunningham (1876- 1947) and David Bear (1846-1917) got “20 coyotes, several badgers, skunks, and opossums.”

In 1915, John Demain, Jr. (1892-1968) and three friends in a Mitchell Six automobile chased and ran down a coyote on the road this side of Garfield. “In the excitement of the chase one member of the party jumped out of the car before it had come to a full stop and got rolled almost as badly as the coyote, but was not hurt.”

I was surprised to read that sometimes a coyote hunt took on aspects of an English fox hunt. “One half mile west of Offerle, on Mat Stegman farm, 15 coyotes will be turned out singly, in the open, to be caught. Three prizes will be given to the fastest dogs. (Graphic, Nov. 17, 1921)

Another method of hunting was described in the Graphic on Feb. 8, 1923: “Pratt is staging the newest stunt in coyote hunting, doing it in an airplane. It remains to be seen whether the wily coyote can fool the airplane raiders or not.”

Coyote hunting included eliminating dens. That same spring, John C. Soice was “still at the head of the class in regard to coyote scalps. Mr. Soice brought in six more puppies yesterday, making 24 young coyotes in less than a week.” (Mercury May 10, 1923)

“Rev. Paul Brockhausen driver of one of the Lewis school busses, stated on Tuesday he saw a pack of eleven in a pasture just west of the Floyd Delay farm. Six coyotes were driven from a field of maize at the LeRoy Ary farm Monday afternoon. Chas. Milhon killed one of the animals and Ary dogs destroyed another. On Sunday John and Joe Bratcher, south of Lewis killed two. (Belpre Bulletin, Nov 23, 1944)

Coyote hunting has not been without controversy. One citizen wrote to Gov. Docking in 1972: “It appears to me that the only folks having problems with predators are those who do not properly care for their livestock.” Landowners have also complained that coyote hunters do more damage in destroying fences and equipment than the coyotes.

From the beginning, coyotes were not legally classified as furbearers in Kansas, and so they could be hunted all year long. The coyote hunting laws are set by the legislature. Bounty payments were stopped in 1970 and poisons were outlawed in 1983.

Because coyotes are mostly active at night, in 2020, Kansas law allowed for hunting from vehicles using lights, night vision and thermal imaging from Jan. 1 to March 31. Special fur harvester licenses are required to trap or hunt and sell the pelts.

I talked to Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism Research Biologist Matt Peek. Peek said that while many people hunt coyote to protect their livelihood, today most people hunt them for recreational purposes as part of an outdoors lifestyle. As a native species the department supports protection, population management and harvesting. He explained that the coyote is ecologically important to maintain a balance in the mice and rabbit population. At the same time livestock and pets need to be protected from their increasing population.