“In order to alleviate the unemployment condition in western Kansas caused by the dry weather and poor crops this spring and summer, Gov. Alf M. Landon today requested Harry Darby, director of highways, to use the first of the Kansas highway money allocated under the Public Works bill in western Kansas.” (Kinsley Mercury June 22, 1933).

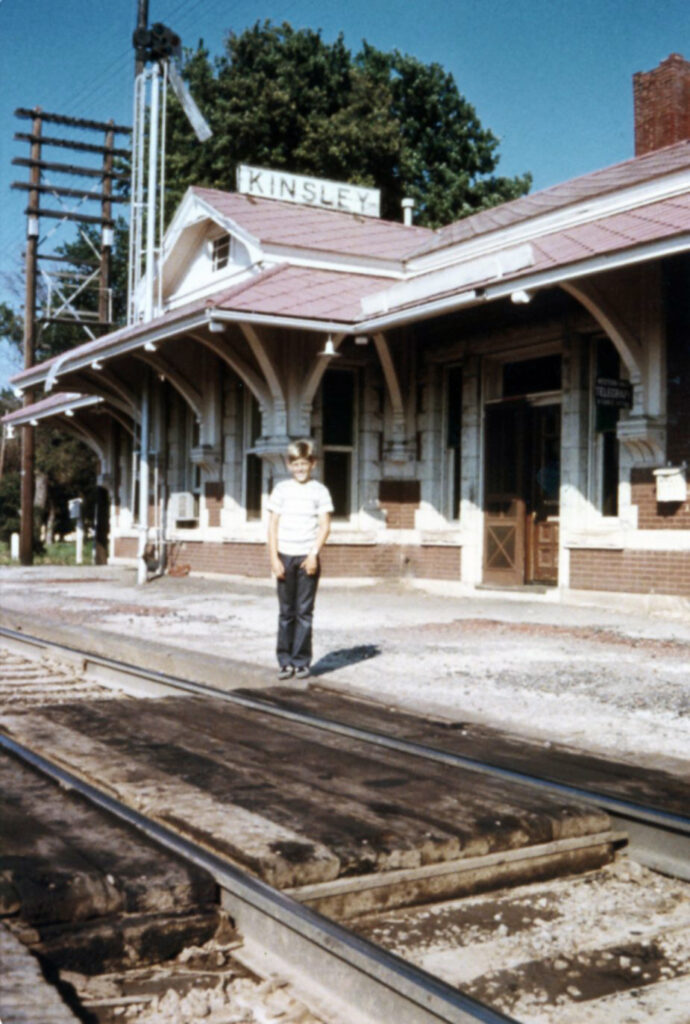

This announcement began several years of highway planning and rerouting in Edwards County. Many people do not know that Eighth St. (not Tenth St.) was the original Hwy 50 South route. The Kinsley Cottage Courts (Quisenberry), old Southside School, the library, high school and three hotels (Sunflower, Grove and American House) were all located along it.

Knowing about this, I wondered what other changes were made and so turned to the library archive to find research done by Gary Jarvis in 1998. As he says in his preface, “This book was originally dedicated to researching the history of the Overpass, but my research led me to go back further to…. the highway construction that took place in Edwards County for a period between 1933-1938 to understand how the decisions were made to construct the Overpass.”

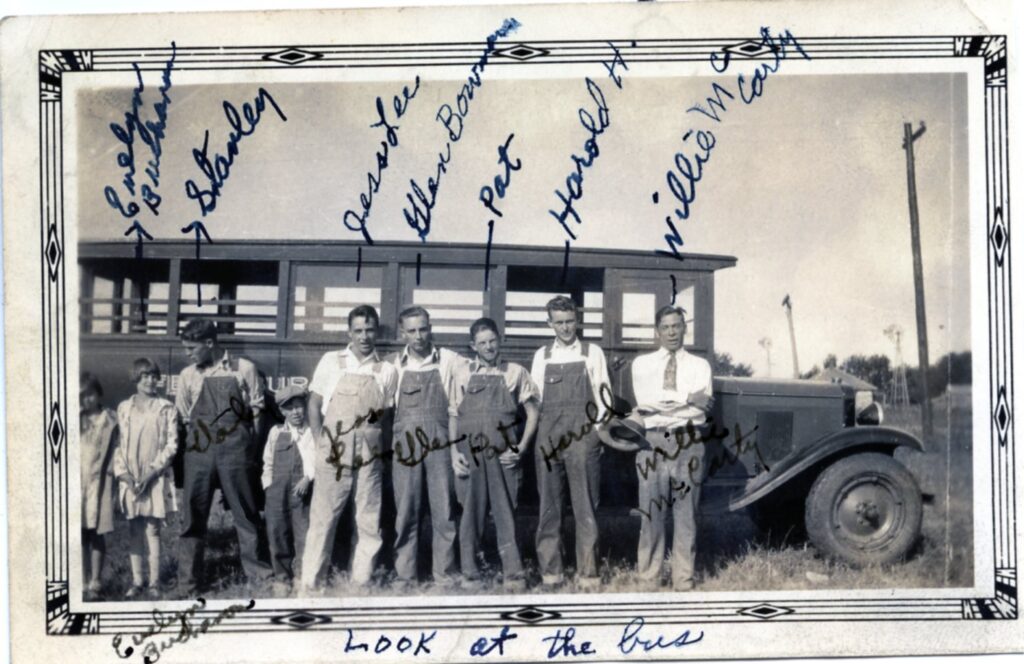

Relief funds from the Civilian Works Administration were acquired to reroute and hard surface highways and city streets, improve country roads and rebuild bridges in the county. The December 14, 1933 issue of the Mercury reported that 346 CWP workers, 9 two-horse teams and 72 four-horse teams would be hired to do all of the these projects.

In order to share the employment as much as possible, a maximum 30-hour work week was enforced. Hiring preference was given to veterans. Unskilled men were paid 45₵ per hour, intermediate grade laborers received 65₵ per hour, and skilled men got 80₵ per hour. Horse teams were paid by the hour at 20₵ for two, 30₵ for three and 40₵ for four.

Widening or rerouting a road required the acquisition of land. The rights-of-way were purchased or gotten through condemnation with payments 1 ½ times of assessed valuation. Buildings were moved or torn down and farmers fences and telephone lines were moved.

In the 1930s, the county highways had different names. In 1927, Hwy 50 split in Kansas with the 50 North branch route going through Garden City, Jetmore, Rozel, Larned, Great Bend, Lyons, McPherson and Baldwin City. Hwy 50 South followed the current Hwy 50 route Dodge City and Kinsley. In 1932, Hwy 50 was the only hard-surfaced road in the county.

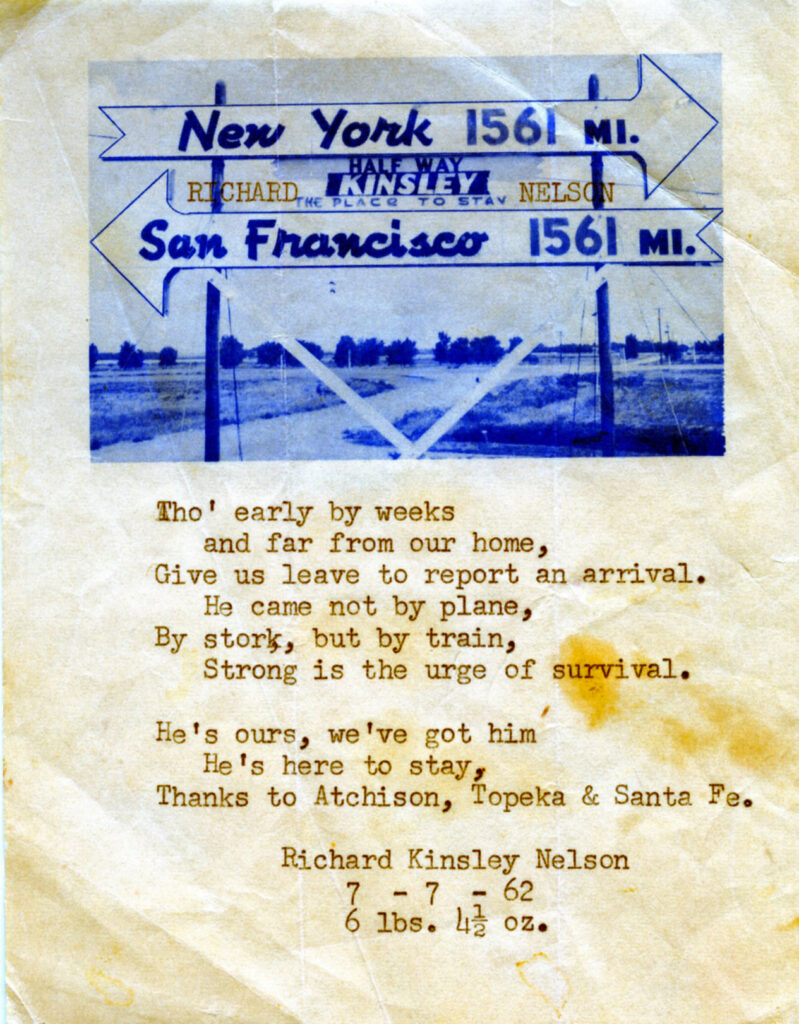

Hwy 56 was originally called Hwy 37, and it ran along the Santa Fe Trail from Larned to Kinsley. Becoming a federal highway required Hwy 37 to be widened from 50’ to 150’. As it came through Kinsley, you may remember from a previous article that the Brodbeck swimming pool by the EZ stop had to be made smaller. Also, an elevator had to be torn down and a gas station moved. In 1935, Hwy 37 was renamed Hwy 45, and in 1955, it was renamed again becoming Hwy 56.

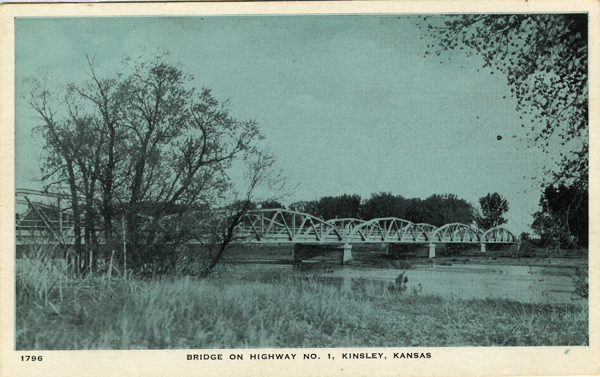

Today’s Hwy 183 was originally called Hwy 1 in Kansas, and it went from South Dakota to Texas. In reading though Gary Jarvis’ notebook of Mercury articles, I learned that the route Hwy 1 took south from Kinsley to Greensburg would be changed in two places. First, after crossing the Arkansas River, it used to be a little west of where it is now before joining back with the existing road at the Parallel. The Anthony and Northern Railroad line ran just a little west of it.

The other place it was changed was two miles south of the Parallel where it makes the 90 degree turn east. At this time, it went one mile further to the east and then turned south on an existing Cannonball Stage route that went into Greensburg. The new route made that turn south one mile west of the stage route so it would meet the road to Coldwater at Hwy 54 as it does now.

Sixty men and 18 four-horse teams began work on Hwy 1 in 1934, and the finished highway was reopened in October, 1938.

Old Hwy 183 (now 100th Avenue) also went north out of Kinsley to Rozel which was located on the old Hwy 50 North (now Hwy 156). Before the hard-surfacing, I read that people preferred to go to Larned on this road as it was in better condition than the old Santa Fe Trail (Hwy 56).

That brings us back to Gary Jarvis’ original research – the why and how of the Hwy 50 Overpass — and the topic for next week’s article.