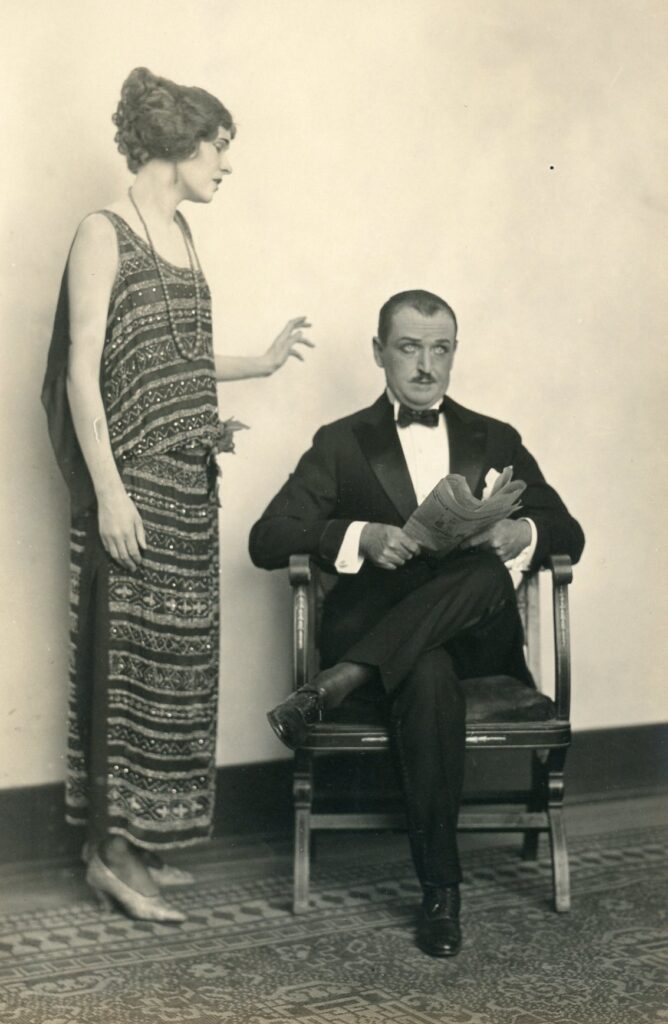

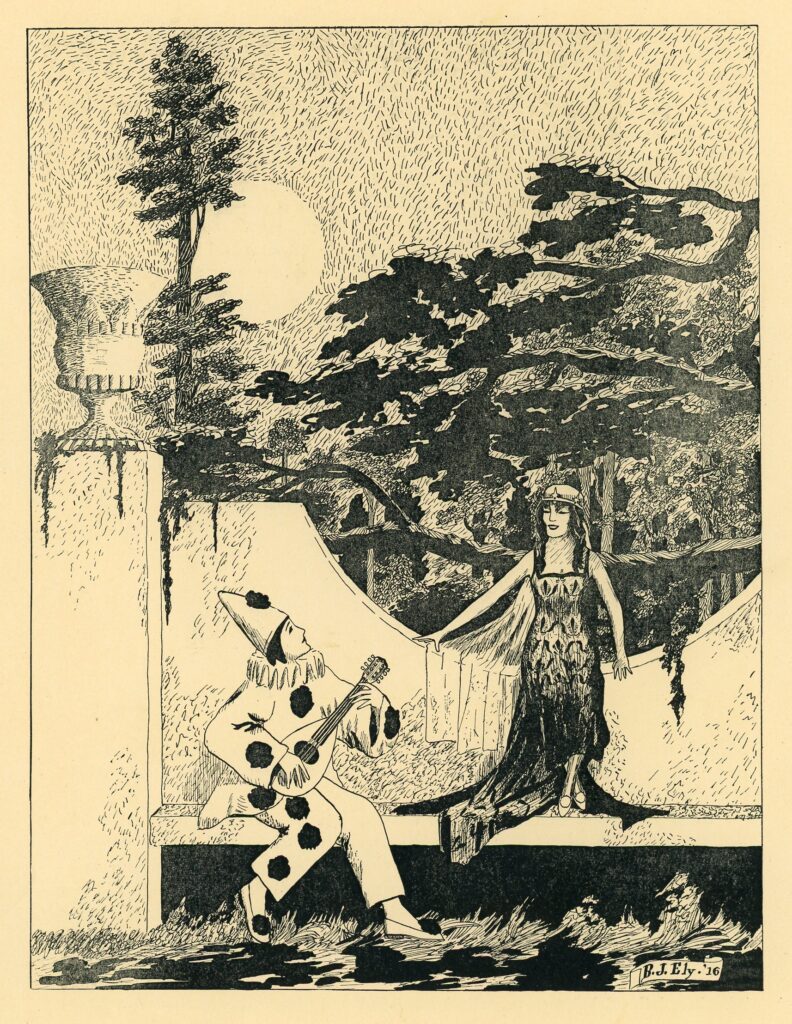

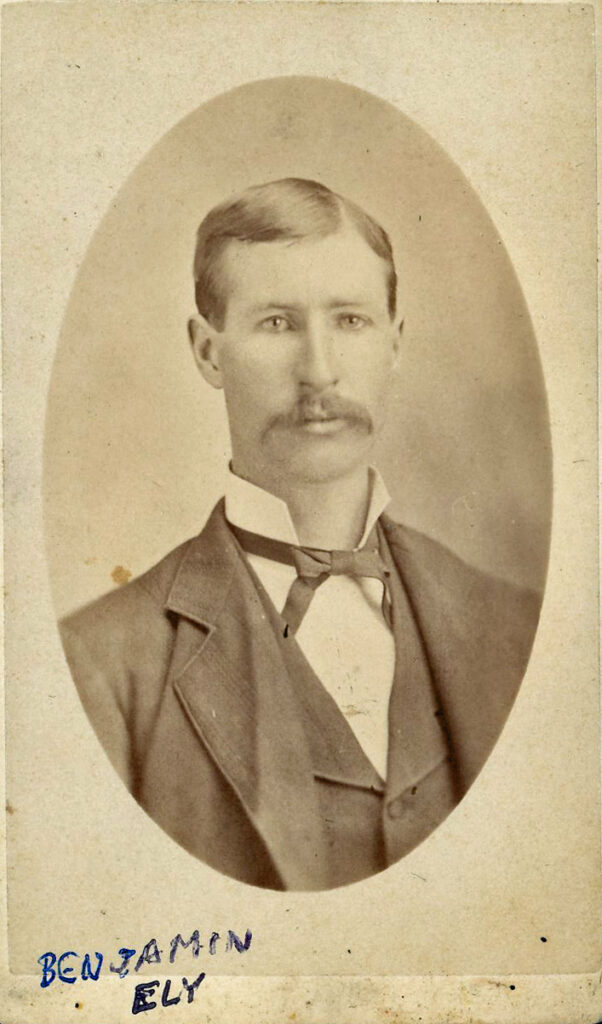

Last week, I introduced you to Sue Bidwell, a talented local actress who was in cast pictures in the Ely box of photos. I wondered what happened to her after performing in Charles Edwards’ plays in 1924. Her life turned out to be very interesting for a Kansas girl.

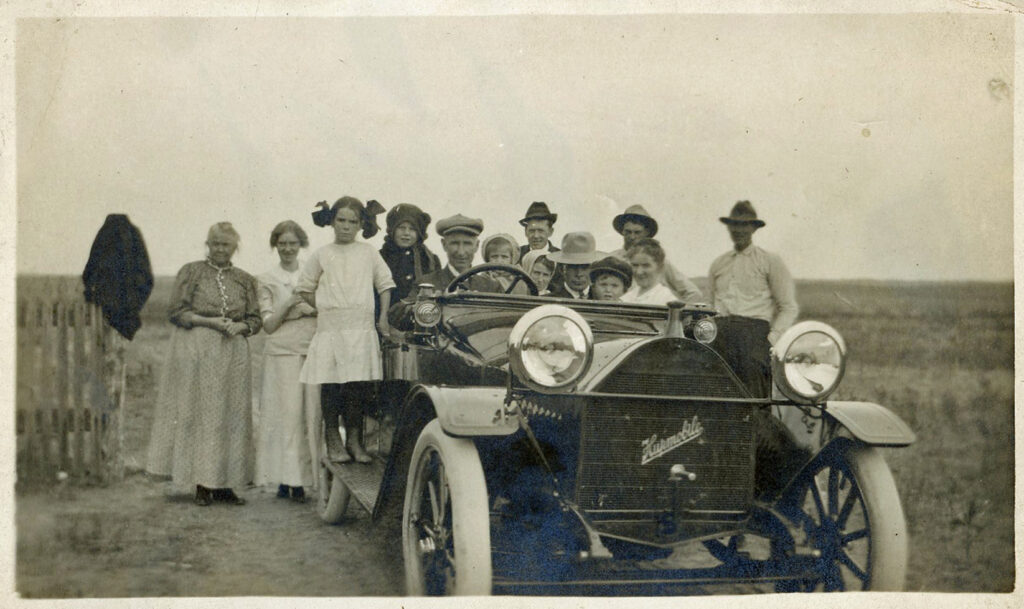

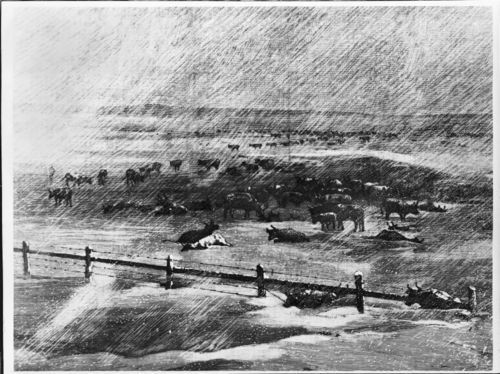

The first Bidwell who came to the area was a cattle-ranching uncle, Edward T. Bidwell. who settled near Coldwater in 1876.

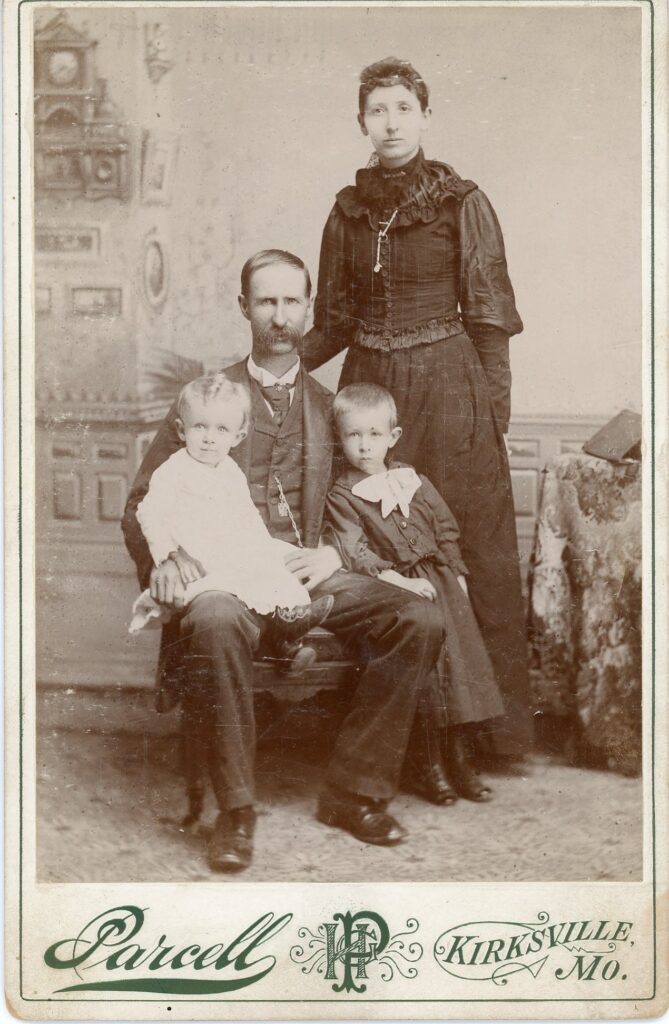

In 1878, Ed’s father, George E. Bidwell, brought the rest of the family to a farm north of Kinsley. One of Ed’s brothers, George H., went into business in Mullinville where he married Matey Harp in 1895. They would have two sons before having their daughter, Sue Jeannette, on December 26, 1900.

Tragically, the next year, George contracted Typhoid fever and died at his father’s home in Kinsley. He left his widow with three young children to raise.

Ed, who suffered a near-fatal fall from a horse in 1884, gave up cattle and went into business with his brother-in-law, John Marsh in 1892 in Kinsley. He and Matey married on Sept. 12, 1903, making Sue’s uncle also her stepfather. T would have two daughters, Myra and Avis.

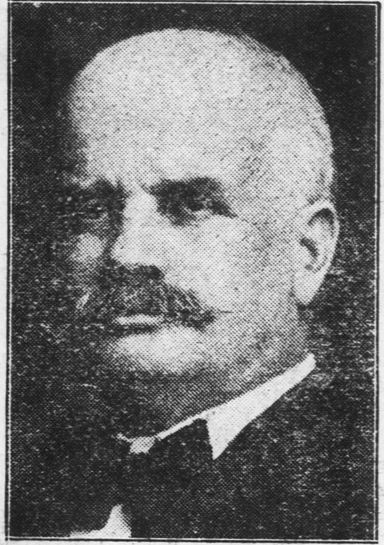

Throughout high school, Sue performed in the plays, was active in debate and sang in the school and church choirs. She graduated in 1919 as the class secretary-treasurer and then attended the University of Kansas. She would be home in Kinsley in the summers to perform in Charles Edwards’ plays. I could not confirm the rumor that she was Edward’s secret love. He was 19 years older than she.

In 1924, Sue was living in Kansas City and acting with the Chanticleer Players. A reviewer from the Kansas City Times reported: “Sue Bidwell and Jay Sinnagan had the leading roles in the playlet (‘Where Do We Go from Here’) and handled them very nicely, except that both fumbled their lines occasionally.” (Feb. 27, 1925).

I could not easily find any other references as to what Sue did after that. It would be ten months later that she would learn of Edwards’ suicide in Tulsa on New Year’s Eve.

It was quite fortuitous that in the summer of 1928 Sue decided to visit her widowed Aunt Sue (Mrs. John Marsh) in Tulsa. There, she met and quickly fell in love with William Ernest Victor Abraham (known as Weva). He was an Irish geologist with the large Burma Oil Company and was lecturing in Tulsa on petroleum engineering.

They married on December 3, 1928 in Los Angeles, and left on a honeymoon spent sailing on a Japanese steamship to Hawaii, the Philippines, Japan, Shanghai, and Bangkok before arriving back at Weva’s home on the Irawaddy (Ayoyarwady) River between Rangoon and Mandalay (Nyaung U) in British Burma (Myanmar). Here she would have servants and enter into the comfortable life of English society.

By 1933, they had three children, Susan, Sally, and Tom. From 1931-1937, Weva was a lieutenant-colonel in the Upper Burma Battalion of the Burma Auxiliary Force. In 1937, he was promoted, and they returned to Dorsetshire, England. That year, they received an invitation to attend the coronation of George VI.

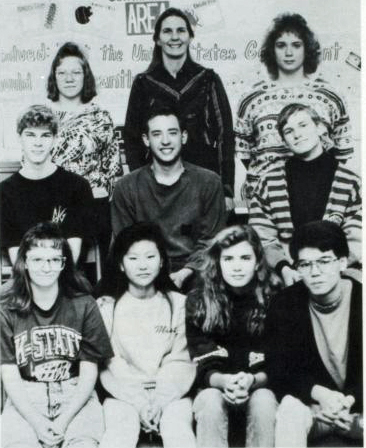

In 1940, Weva rejoined the army as a second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers. The German blitz drove Sue to return with her children to the safety of Kinsley to stay during the war. Weva would remain behind to serve in Greece and Egypt.

On August 15, 1943, the Kansas City Star looked back on the refugees stay here during the war. When they arrived the children “spoke with a distinct British Accent…. Now (their) command of American slang is complete and thorough…. Susan has learned to make her own clothes and play the piano. Sally sings in the Episcopal church and the Congregational church choirs and belongs to all the small girl activities in town. Tom is an enthusiastic Cub Scout who has just learned to do high dives. Their mother keeps house, no small chore in a community where groceries are no longer delivered. She also works in a Victory garden of her own sowing, is Scout Mistress of the Kinsley Cub Scouts and takes them swimming once a week in the town swimming pool….”

“For more than a year Mrs. Abraham was unable to receive any money from her husband, Great Britain having a stern law against exporting any money. She helped make up for the embarrassing lack of cash by giving lectures in various towns in Western Kansas on what the war meant to Americans, life in Burma, and similar subjects on which she knew plenty.”

In the fall of 1942, Weva flew on a military mission to Washington in the same “sleeping car plane” that had carried Winston Churchill to Moscow a few weeks earlier. On that trip, he was also able to visit his wife and children in Kinsley.

Weva rose to the rank of Major General, and in 1942, he became Sir William when he was awarded Officer in the Order of the British Empire because of his actions in Tunisia during the war.

After the war, the Abrahams lived in Kencot Manor House built in 1508 in Gloucestershire. In 1955, they entertained the Burmese Prime Minister U Nu and his wife there.

Sue kept in touch with her family in Kansas until her death on February 19, 1965 at the age of 64. She is buried in Hillside Cemetery.

Weva would marry again, and his second wife would see him knighted in 1977 by Queen Elizabeth