John W. Pixley was born in 1894 and was a sophomore at Kinsley High School in 1917. At the time he was drafted in February, 1918, he was living at the YMCA in Newton. He would serve 15 months, becoming a sergeant of the 42nd Transportation Corps working with the railroad. In June of 1918, Pixley found himself on a transport ship crossing the Atlantic.

“….To begin with, immediately after leaving port, I was initiated into life on the water by getting sea-sick, which stayed with me two days. I have been sick in a number of different forms, but oh joy, if ever one felt miserable….I had to feed the fish several times before I finally overcame it….It may seem to you that seeing so much water would be tiresome and while I admit it is some puddle, yet there are many things to interest ‘dry land turtles.’ You can readily understand that it would be impossible to carry enough fresh water for washing purposes for such a large gang of men, so it is necessary to use salt water to wash with. The first thing we discovered was that ordinary toilet soap won’t work with salt water at all. Fortunately however, the ship is equipped with a canteen where the men may buy tobacco candy, soap, pickles, canned beans, peanut butter, etc., and we were able to procure a salt water soap made by Colgate which works fine with ocean water.” Kinsley Graphic, August 15, 1918

I must admit that I did not know regular soap did not work in salt water until reading this letter. I tried to do a little research, even chatting with Colgate, and could not definitively discover what Colgate product this was. It may have been a lye soap Colgate produced called Octagon Soap.\

Soldiers’ letters home were all read and censored usually by an officer and sometime by the chaplain. The soldier was not allowed to write anything which would give information to the enemy, such as location, movement of troops, and size of troops. They also could say nothing that the enemy could use to bring down the morale of the troops or that would affect the morale back home. Many of the letters that were published in the paper mentioned the censorship, and what Pixley wrote was typical.

“I am beginning to understand why the boys do not write much from here. There is so much that is forbidden being included in correspondence that it is some job to write anything and keep within the rules, at least I have found it so. There is so little to write about except one’s own activities, and the censorship rules are so strict in this respect that it leaves so little to write about. However, one should not complain about that for if such rules were not enforced, information of untold value could be communicated to the Hun, whom it is our job to lick to a standstill and in the shortest time possible. So you will have to satisfy yourselves with what I write (and what the censor) will pass, until it is over and I am home again, then I will give it to you in detail.” (Published August 8, 1918 in the Kinsley Graphic).

I found some other interesting facts about the mail during World War I in an article published by the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. In April, 1917 postal service underwent several changes. The rate for a letter was 2¢. To help pay for the war, it was raised on November 2, 1917 to 3¢ and remained that until July 1, 1919 when it was returned to 2¢.

Both men and women were rural mail carriers in the early 1900s, but only men were postal carriers in the cities. But with the scarcity of men, “…the Post Office Department experimented with appointing women as mail carriers to replace the men. The ‘experiment’ began in December 1917 in eight cities with the largest post offices – by the war’s end, several other cities had also appointed women mail carriers. Most of these women gave up their positions to returning veterans once the war was over.”

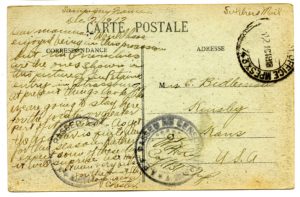

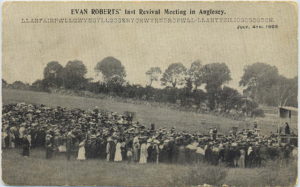

During World War I, the U.S. Army Post Office (APO), was begun mainly because the War Department did not want to share the location of troops with the Post Office, which made their job very difficult. The APO operated independently from the USPO. Congress also decided to grant free postage to those serving in the armed forces. These were simple marked “Soldier’s Mail” as in the postcard below from Chester Bidleman. The censors stamp can also be seen on it.