Today’s soldiers have FaceTime, Skype, email, and cell phones to keep in touch with their loved ones when they are away. The World War I soldiers had none of these. Soldiers and their families communicated through letters.

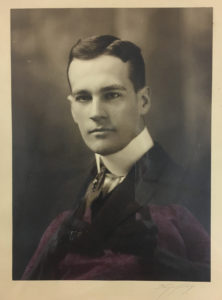

Gilbert Lewis was one soldier who wrote home. He was the son of the editor of the Kinsley Graphic and had graduated from Kinsley High School in 1910. He got his law degree from Georgetown University in Washington, D.C. and began practicing law in Pittsburg, KS. The day after the U.S. declared war on Germany, he enlisted. He was 24 year old when he reported for duty at Fort Riley in early May, 1917.

Gilbert sent a letter to the Pittsburg Daily Headlight, which they published. On May 21, 1917, the Daily Headlight reported that “Uncle Sam has put the news lid on Fort Riley. An order has been posted in the reserve officers training camp that no officer or enlisted man shall furnish correspondence to any newspaper.”

Because newspapers continued to print letters, I am guessing that it was OK for friends and relatives to take the letters they received to the newspaper for publication. Soldiers could just not be war correspondents. No more of Lewis’ letters appeared in the Daily Headlight, but they were published regularly in the Kinsley Graphic.

In early July, 1918, Lieutenant Lewis was in France. He wrote “I’ve had a new job wished on me in addition to my regular duties. I am town mayor altho I still wear Lieutenant’s bars and have that salary. Have charge of the handling of the billets of troops and officers and the first thing I did was to billet myself in a nice room vacated by the departing town mayor. It is a dandy clean room upstairs, simply spic and span as can be, and down stairs the people run a bake shop and are nice and friendly. They gave me some warm water for a bath tonight. On the bed is a thick feather tick and you almost sink out of sight in it, but my how you do sleep….The way the job came, they sent to Co. H. for an officer to relieve the departing mayor, and being the Junior Lieutenant the Captain picked on me….The mayor must act as a buffer between the civilian and military authorities, and up to date, I have settled fifteen hundred rows more or less. Of course an interpreter goes with the office. This morning I had a time assuring an old Frenchman that the gas engine of the surgical car would not shake his building down, and another that the boys would not play ball in his pasture any more. Also asked an old lady if we could have religious services on her field and she said ‘sure” in French. (Kinsley Graphic, August 8, 1917)

The letter published the following week told of another duty the mayor had. “Today, July 14, is a big day for France, the anniversary of the taking of the Bastille. They celebrate as we do the Fourth of July, and today we are to help in their celebration by having a parade. As town mayor I am to go with a party of officers and call on the Mayor and present America’s compliment and say a few nice things, and then when the excitement is over the rest of the day is ours.”

A letter published in the September 26, 1918 issue of the Graphic, reveals that Lewis has been in the front lines in France and has now been moved back to support. (Troops were continually rotated in and out of the front line trenches.) He relates the following story:

“My nice trench coat has been repaired and does not look so bad. It was hanging in the shack we were staying in when we were in support. The place was shelled and riddled with bits of high explosive shells. At the time I was in the front line trenches. That night we all slept in dugouts though, just to be safe. One day Wick and I were gathering plums in a deserted village between the support lines and the front line trenches and about two miles from the German lines. Wick insisted on climbing into the trees that were exposed to the view of the Germans and I suggested to him he might be observed, but he insisted we were so far away the Germans could not see us. Well, I don’t know whether they did or not, but pretty soon I heard the whine of a shell coming, and you can sure tell when they are headed in your direction. Wick jumped down out of the tree and I was already on the ground. The shell whizzed by right over the tree and exploded about 150 yards beyond. Strange to say we gathered no more plums but wended our way homeward to the support. Wick allowed as how he didn’t mind being sniped at by the Germans with a rifle, but when they took to sniping with three inch cannon, it was time to call off plum gathering for the day. But you don’t need anybody to tell you to duck when you hear the whine of those shells coming. It sounds lots nicer to hear our own artillery shells sing as they toward the German lines.”