The Wright brothers achieved the first powered, controlled, sustained airplane flight at Kitty Hawk in 1903.

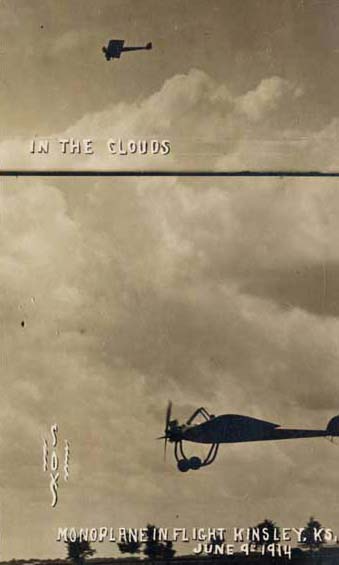

Clyde Cessna’s monoplane made its first successful 5-mile flight and landing at the point of departure in Oklahoma on December, 1911. That began the development of several monoplanes by Mr. Cessna between 1912 and 1915. To make money, the “Birdman of Enid” often flew his aircraft at community events including the Old Settlers Picnic in Kinsley in June, 1914.

It must have been thrilling to witness this early flight. F. H. Lobdell, editor of the Kinsley Mercury, described it this way:

- “Promptly at three o’clock the air ship was pushed out to its starting point in the right field of the ball ground. Trundled along the ground it appeared awkward and helpless. There was a slight delay in getting the crowd out of the danger zone, then the engine was started. It missed fire occasionally during the first few seconds, but the steady roar soon told that it had struck its stride. The aviator moved a lever and the bird like form started. For perhaps 1000 yards it run on the ground, then the plane was shifted and it took the air gracefully and sailed away toward the river. In a few minutes it was almost lost to sight against the fleecy white clouds in the horizon….

“….The crowd had gotten too far out to permit a landing in safety on the ball ground, so Cessna lit in a corn field about three quarters of a mile east. It happened to be a listed field and the wheels digging into the soft ridges overturned the machine. Mr. Cessna was not injured and only a small piece was broken from one of the propeller blades.” (June 11, 1914)

Commercial development of airplanes was delayed by World War I where they proved valuable for both aerial observation and combat in Europe. Around here, it was a rare and exciting event when a plane was spotted. The Kinsley Graphic reported that in late October, 1917, the citizens of Jetmore saw a plane with lights plainly visible passing over the city. “…it is well known that every air machine flying in the vicinity of that city is equipped with Delco farm lighting system, so that accidents in alighting may be avoided.”

One of the dangers of early flying was finding a place to land. Landing in fields and pastures was hazardous. Newspapers noted incidents including an airplane “that went through Kinsley a short time ago was wrecked in a cottonwood tree in Garden City.” (Graphic, Sept 4, 1919)

In December, 1918, three government airplanes were sent out to plan an aerial mail route. Preparations had to be made for a landing field in Kinsley. Mayor Ben Ely planned to have a large white banner hung to show the location of the field and the direction of the wind. A bulletin board was placed on main street announcing the chosen location, and giving a warning for everyone to keep outside the track until the planes landed.

One plane was in need of repair and could not leave Dodge City. The second plane arrived about noon and landed south of town in Harry Rapp’s alfalfa field where it remained for an hour before flying on to Pratt.

The third plane flew to Garden City before making the flight back east to Kinsley. It arrived about dark and landed in a listed field east of town. The home guard was called out upon to guard the plane through the night.

About ten o’clock Sunday morning the pilot took off. “He came up over the city and put on a show that delighted a large audience and seriously interfered with the attendance at Sunday school, but then we can have Sunday school every day while such an exhibition of fancy flying may never again be seen here.” (Graphic, Jan. 2, 1919).

“They flew over the town, doing stunts, showing what the planes could do. They turned over and over, both backwards and forwards and sideways and flew upside down. They made a spiral spin and landed, after which they took off for Pratt.” (Mercury, Jan. 2, 1919)

Six months later, the Old Settler’s Picnic arranged for Pratt airplane #1 to be part of their celebration. Unfortunately, when it took off, the engine failed and the plane came down. “One wing struck a little cottonwood tree, throwing the machine around so that it struck sidewise in the corn field just east of the road and broke the propeller, stripped off the running gears and broke three sections of the wings. The pilot estimated the damage about $2,500. Neither of the men with the machine were injured except in their feelings.” (Graphic, June 26, 1919)

- I want to relate one more story about an early flight taken from the library’s collection of oral histories. When I interviewed Lewis resident Jack Wolfe (1916-2017), he surprised me by saying, “I got my first aircraft ride with Charles A. Lindberg.” His family was homesteading in Colorado, and he told the story this way:

“It was feed planting time. Dad was out in the field planting feed for the cattle and horses in the fall. It was in the paper that Eddie Brooks was going to be in town. He was a barnstorm pilot. He was going to take rides off of airport hill there in Flagler. Dad says, ‘When I get done drilling, we’re going to unhitch these horses and go up and watch them boys fly.’

“Well, they were flying continually. Everybody wanted a ride. A little before sundown, Dad walked up to old Eddie Brooks and he says, (You know, I was just a little fellow, seven years old. I was small for my age) he walked up to old Eddie, and he said, ‘Would you give Jack and I a ride for one fare?’

“Can’t do it.”

“So he walked over, there were two pilots and two planes, he walked over to the other guy, a big old tall, slim guy, and they got to visiting. And Dad says, ‘Would you take Jack and I for a ride?’

“Get in!” he says, “I’ll give you a ride, five dollars.”

“He took us up around and over the city and back down. It wasn’t over five minutes, I suppose.

“But after Charles A. Lindberg flew the Atlantic, it came out in the paper that ‘Charles A Lindberg had been here with Eddie Brooks.’”

If you’re interested, more local history involving a club of flying farmers and the development of our airport can be discovered in the files at the Kinsley Library.