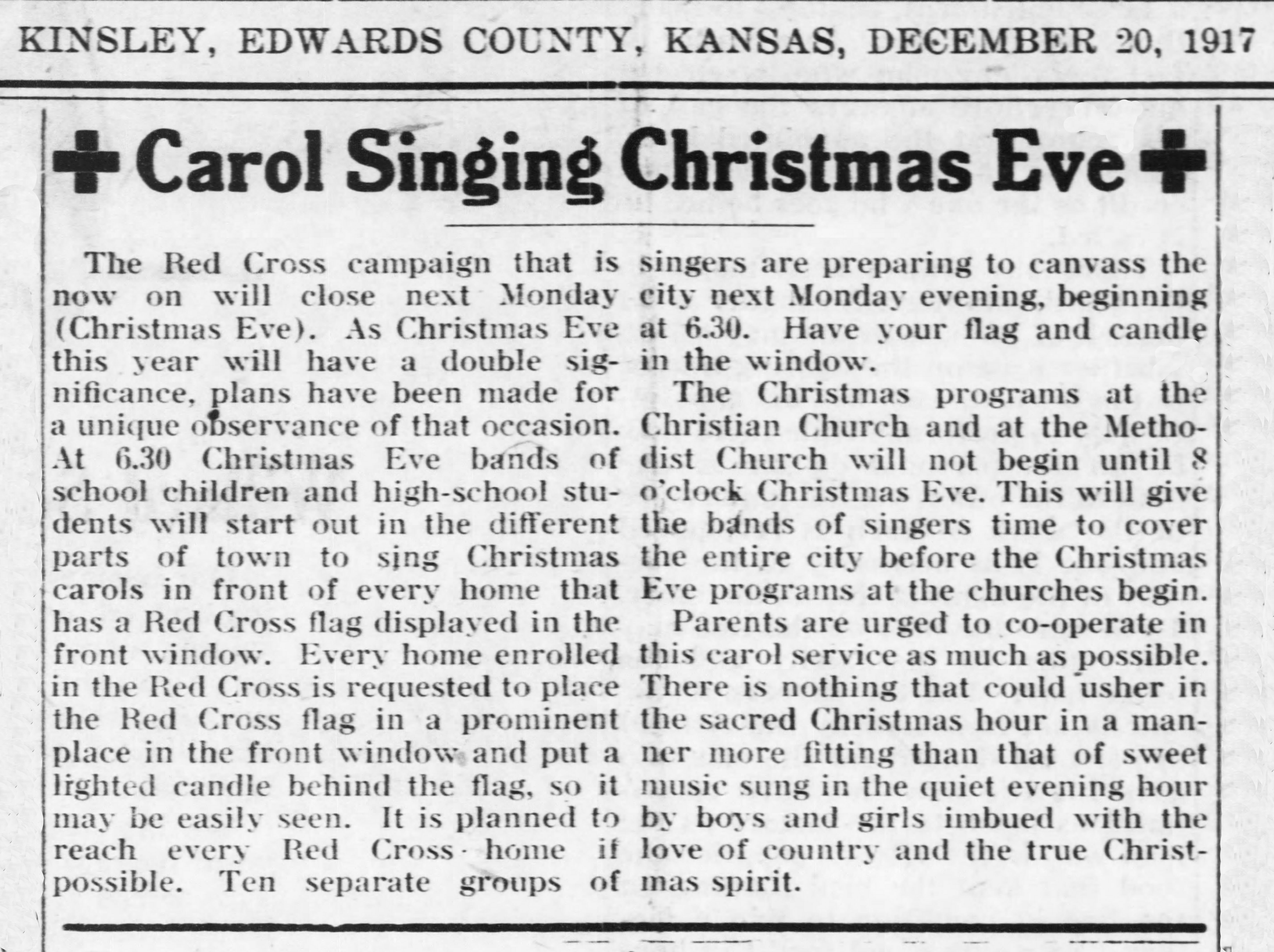

“You are hereby notified that the registration of German alien enemies is to commence at six A.M. on February 4, 1918 to continue…up to and including the 9th day of February, 1918 at eight o’clock P.M….Persons required to register should understand that in so doing they are giving proof of their peaceful dispositions and of their intention to conform to the Laws of the United States.” Kinsley Graphic, January 31, 1918.

One hundred years ago, all non-naturalized males over the age of 14 were required to fill out a Registration Affidavit of Alien Enemy with the United States authorities as a national security measure. This registration focused primarily on non-citizen German residents, but included Italians and other nationalities, as well. Non-naturalized female enemy aliens were later required to register using a Registration Affidavit of Alien Female form in June, 1918.

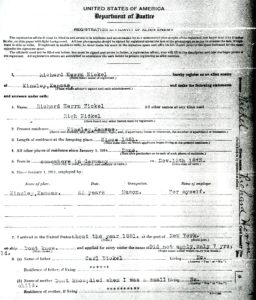

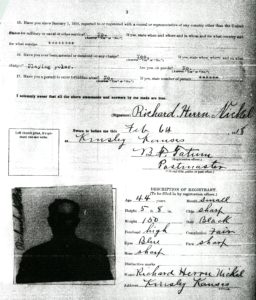

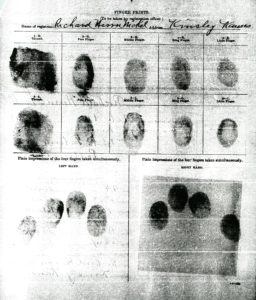

The information on these registration forms included immigration dates and places, birth and parentage, names of family members, address, occupation and employer; residents were also asked if they were sympathetic to the enemy and the names of any relatives serving in enemy forces. Registrations included a physical description, fingerprints and photograph for the person.

According to the National Archives, most of these Enemy Alien records were destroyed by authorization of Congress in the 1920s, but some survive, including the forms for Edwards County which are on microfilm at the Kansas State Historical Society. We borrowed the film and printed the 44 forms which we now have in our archive.

Richard Nickel was one of those who was required to register. From his form we learn that he was born in “Somewhere in Germany” on November 15, 1873. His father was Carl Nickel and he didn’t know the name of his mother as she died when he was young. He came to the United States and Edwards County in 1881 at the age of 7. At the onset of the war, he had been in this country 36 years. He was married to Ellen .They had no children between the ages of 10-14. He had been arrested once for playing poker. He had started the naturalization process in 1898 but must not have finished it.

Following are the names of the men who registered as alien enemies in Edwards County:

Margan Breitenbach, John Hackenbroich, Charles Weidekind, Joseph Wolf, Henry Ditges, August Neidig, Erich Griep, John Grybowski, Herman Gutsche Sr., Herman Gutsche Jr, John Havas, Henry Herrmann, Julius Krenzin, Richard Nickel, Oscar Grimm, Frank Mauler, Herman Scwarz, John Haas, August Munchow, Erich Munchow, Henry Ploger, August Ploger, W. C. Ploger, Henry Salm, John Salm, Frank Scholtz, and Willie Tuchtenhagen.

Below are Richard Nickel’s registration forms.