Christmas is a time for traditions. Until a few years ago, the traditional Kinsley community Christmas tree was placed downtown in the center of the intersection of Marsh Ave. and Sixth St. This tradition had to be abandoned when it was deemed a traffic hazard. But I was curious about when it began.

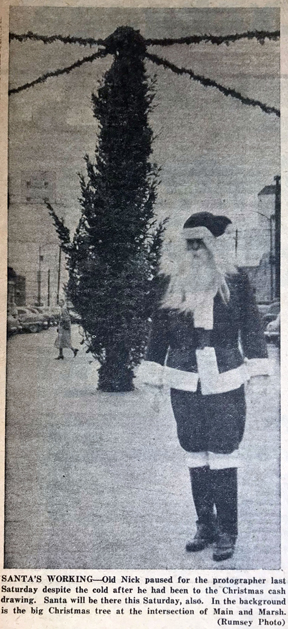

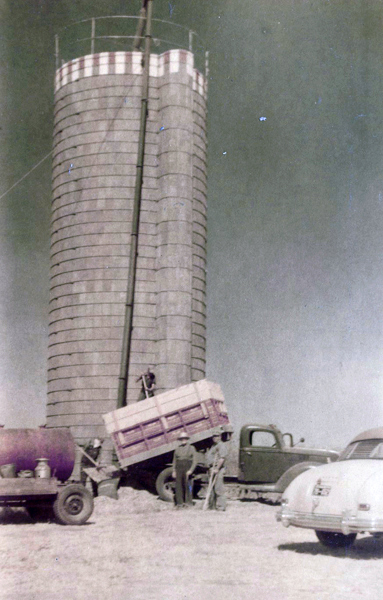

I knew it went back at least to 1963 because the library archive has a picture from Ed Carlson’s family scrapbook of the tree being put up that year. Ten years earlier, Kinsley Mercury published a picture in 1953.

Last week, Melanie Wheeler happened to be in the library when I was wondering out loud about the tree. She left the library and asked her father, Harold Burkhart. He remembered the tree being there a few years after he moved to Kinsley in 1944.

I then called Charles Schmitt who said he could remember a tree being there when he was a small boy in the early 1930s. At that time, he remembered a half-barrel being filled with sand and used to hold the tree upright.

Articles in the Graphic in both 1929 and 1930 reported that there were four Christmas trees, three on Sixth Street and one on the corner of Colony Avenue and Seventh St. However, they do not say if one was in the Marsh St. intersection.

I kept reading back in time and finally found in the December 19, 1919 Graphic what I was looking for. “The community Christmas tree is to be managed by the Red Cross,. . . . A large tree will be placed square at the intersection of Sixth street and Marsh avenue and the crowd will gather for a carol and a song at 7:00 o’clock Christmas Eve.”

I discovered other things about Christmas trees and lights. The stock market crash ushered in the depression, but a 1929 headline that Christmas read, “Our City the Best Lighted in the Country.” It described “strings of colored lights on Main Street from the Hupmobile (317 E. 6th) and Nash Garage to the end of the street, down Niles Avenue to the end of the first block, down Colony Avenue past the school house, down Marsh past the Britton Garage (622 Marsh), and north on Marsh to the City Hall (507 S. Marsh).

“The lights make the down town streets like fairy land with lights. In the foggy evenings and mornings, they are especially beautiful. More than 600 lights were used in the plan for loops of lights along the streets, with strings across the ends of each street continuing down the next.

“Monday night the cars were as thick as if a circus was in town. Many of the individual merchants are putting Christmas trees in front of their places of business and lighting them which adds to the beauty of the street at this season, when the world wants to be happy.” (Graphic, December 12, 1929)

Outdoor home lighting began as early as 1922 when James M. and Cora Lewis wrote about their house, “The Three Winds” (802 Niles Ave.), having a lit out-door Christmas Tree which the neighborhood children enjoyed every night for a week.

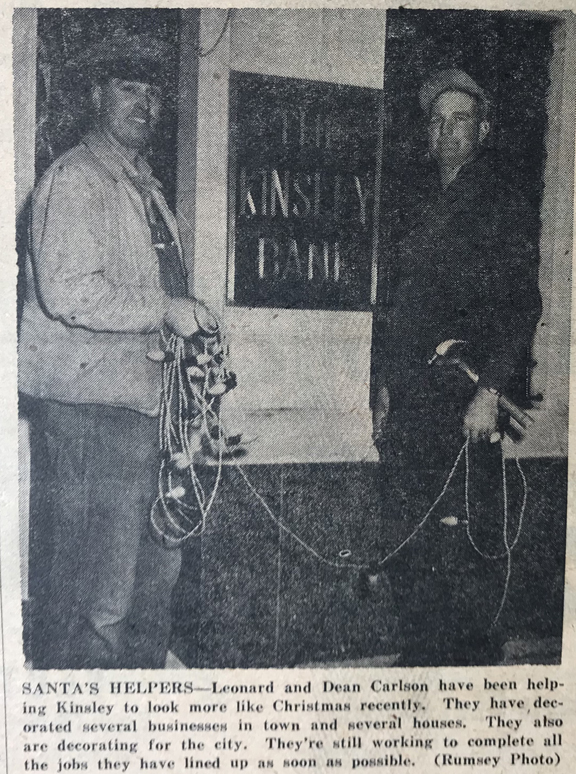

The first year for a home lighting contest was in 1949, and it offered three prizes of $10, $5, and $3. I read that in 1953, Leonard and Dean Carlson were helping the city and many businesses and individuals put up their lights.

Ed Carlson, Leonard’s son, remembers that “All the strings of lights were custom made by Dad and Dean. They would order in the twisted, cloth-covered wire, and two piece sockets that screwed together over the wire at the desired spacing.

“Our house (916 E. Sixth) had green lights, Bobbie’s (Williamson’s, 919 Sixth) directly across the street, was red, and Mrs. Spitze (919 Sixth) next door east was blue. The Swedlund house (905 Marsh) had the nice rounded roof on the front, south of the front door, and they always installed Santa’s sleigh and his reindeer.”

In September, 1953, Evelyn Carlson, Leonard’s young wife and Ed’s mother, died after a year-long illness. That December, Mrs. C. E. (Bobbie) Williamson touchingly wrote the following in the Kinsley Mercury.

“Somehow I feel the Christmas lights are a glowing tribute to my lovely neighbor lady that lived across the street.

“Last year – her whole neighborhood felt it would be her last Christmas, and because the lights made her so happy and their home was done so beautifully, everyone went all out on Christmas lighting, down here in our east end of main street.

“Somehow, I was so surprised when Leonard began a month ago to talk about Christmas lights. Talking with the first happy glow I’d seen in his eyes for a long time—which somehow seemed a lesson of inspiration. So now I feel each and every Christmas light is a glowing tribute to her memory. Incidentally, the street lights are the nicest they have ever been.”

This year, when we are all suffering with isolation and loss, maybe all the colorful lights on the houses, streets, and trees of Kinsley can also serve us as reminders of those we hold in our memories.

And may we still take to heart today what was written during the depression in the Graphic. “What we all need to feel is that all we need to be normal is to feel cheerful, and Christmas should be a time for looking on the bright side.”

.