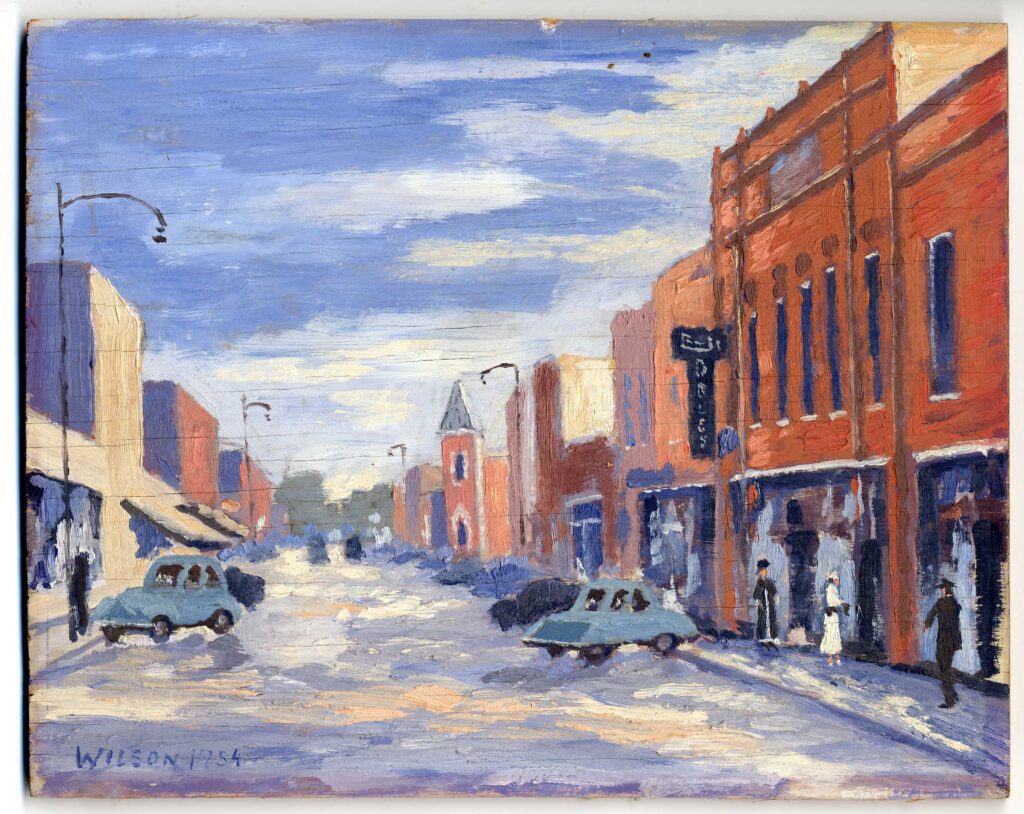

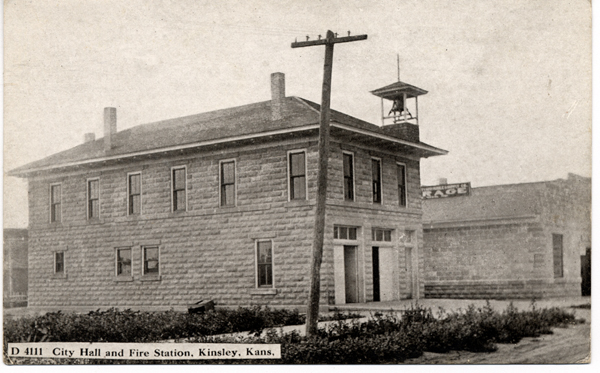

Will you be wearing green this Thursday? As the saying goes “Everyone is a little bit Irish on St. Patrick’s Day” so you may very well choose to do so. The people who settled Kinsley were not Irish immigrants, but the celebration of this holiday was observed from the earliest years.

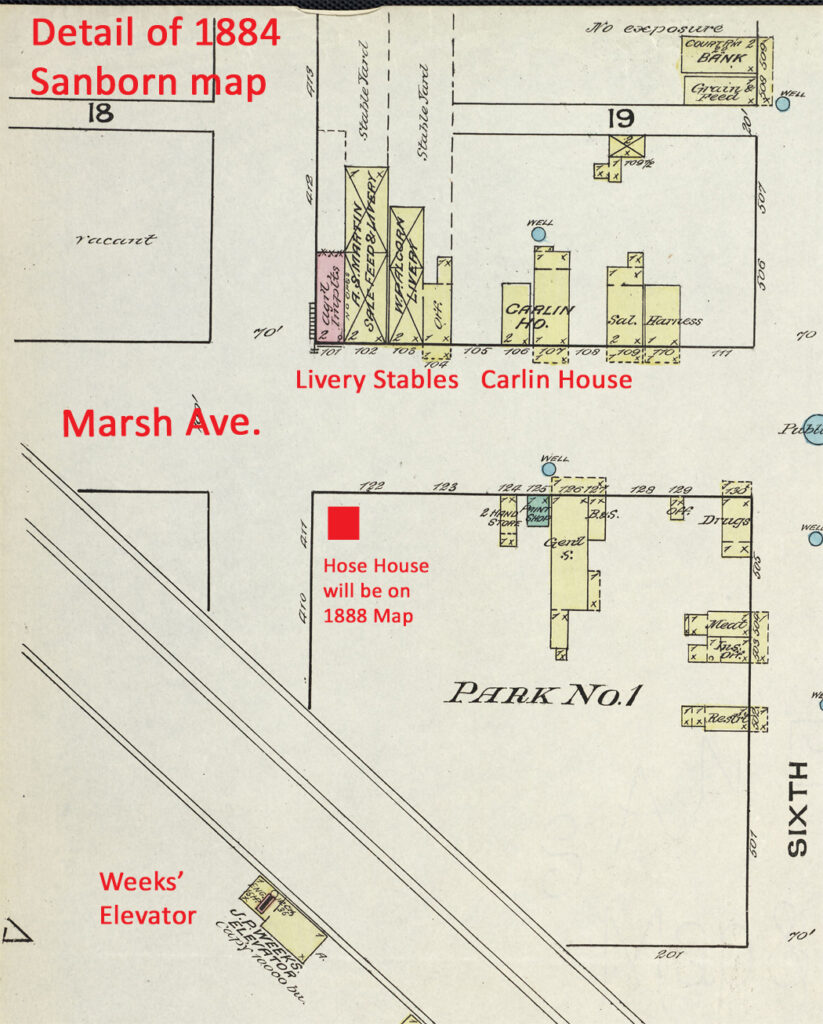

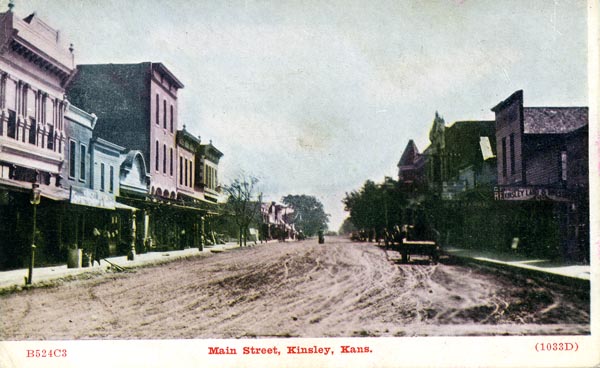

I found the first reference to the tradition in the March 20, 1879 issue of the Edwards County Leader. It reported that a dance had been held at Gem Hall (upstairs at 217 E. Sixth St.). Forty couples attended and it raised money to support the city band.

I’m not sure why, but this holiday was often used to raise funds. On St. Patrick’s Day in 1896, the Congregational Church ladies held a dinner and entertainment for the price of your age.

“This birthday party is given to you

‘Tis something novel, ‘tis something new,

We send to each this little sack.

Please either send or bring it back

With as many cents as years you are old

We promise the number shall never be told.

If any object their ages to tell,

Please put in one hundred,

‘Twill do just as well.

Kind friends will give you something to eat,

And others will furnish a musical treat,

The Cong. ladies with greeting most hearty

Feel sure you will come to your own birthday party.”

The next week, the Graphic editor remarked that “High Bingham is bankrupt since St. Patrick’s Day but thinks he got his money’s worth. The ladies are thinking of charging him two cents a year next time.” Hiram C. Bingham was 67 at the time.

A similar fund-raiser was held three years later by the Methodist Epworth League, a group made up of 16-35 year-olds. Their invitation was to a ‘”Measuring Social” where participants were asked to give three cents for each foot they were tall for an evening of “music and song, recitation and pleasure”. (Graphic, March 24, 1899)

In 1903, one dollar got you admitted to a St. Patrick’s Day concert held at the opera house to support the city orchestra. The next year, the city band provided a concert to support raise funds.

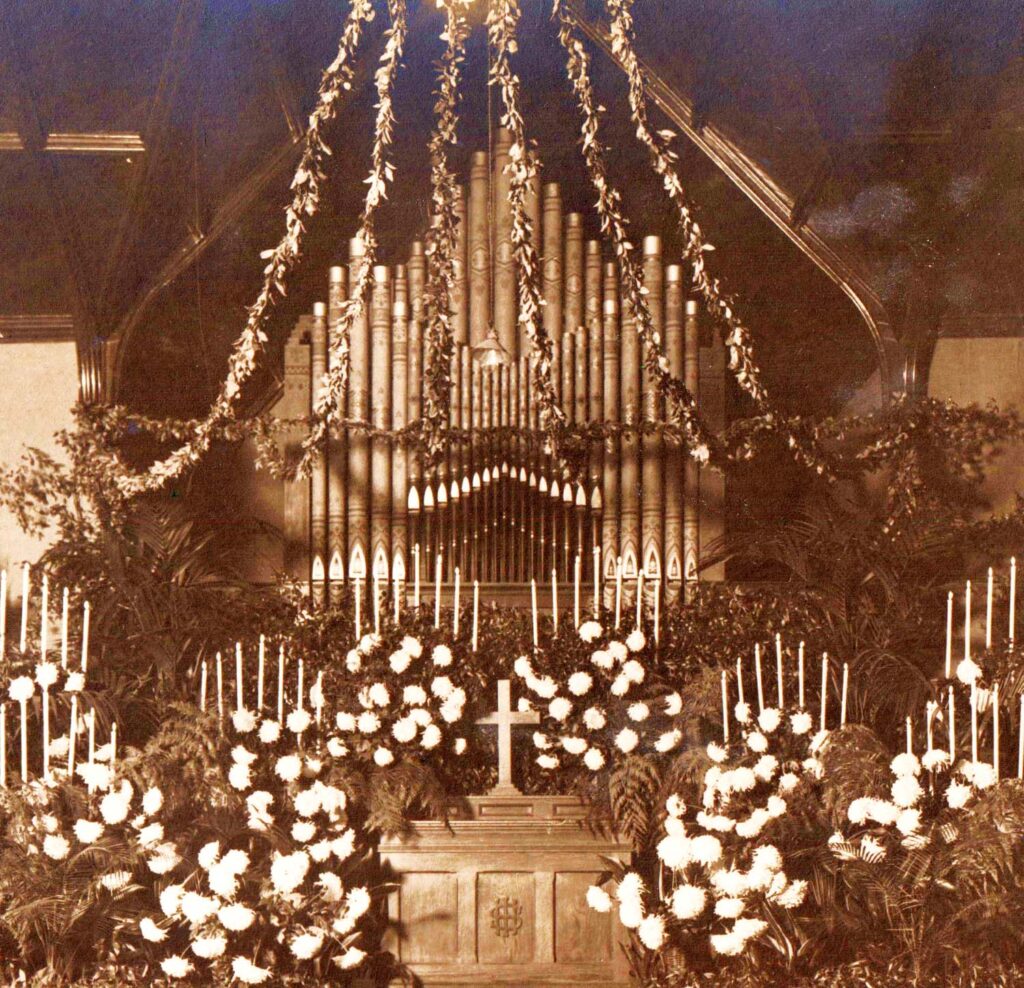

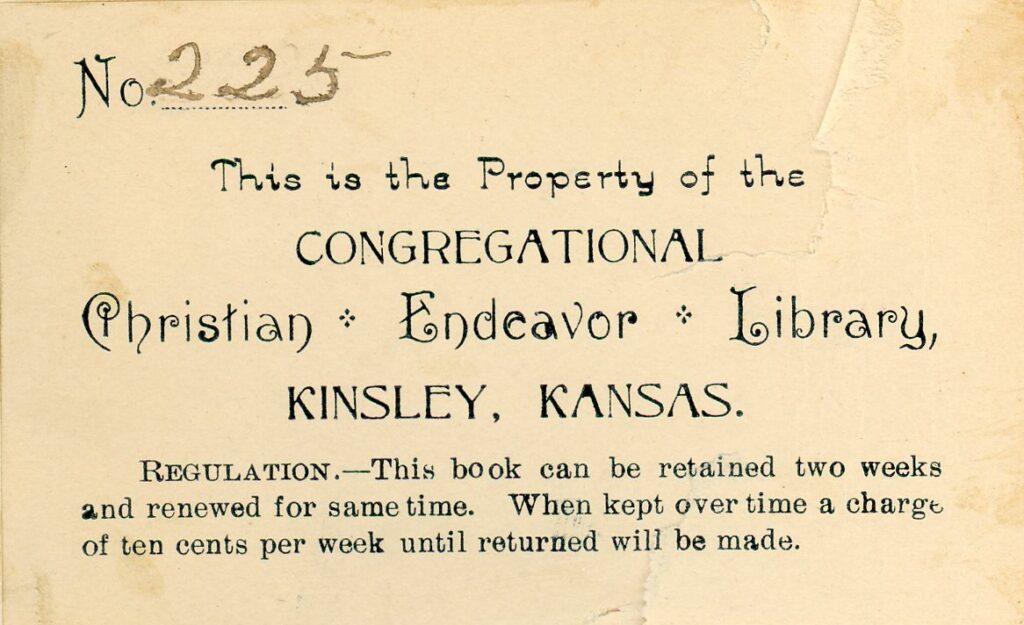

In 1906, the Congregational Christian Endeavor group had their Paddy’s Day fund raiser in order to purchase new books for library. At the time the library was located at the church.

In 1903, a benefit was held on St. Patrick’s Day to raise funds to buy books.

Kinsley hostesses often used St. Patrick’s Day as an occasion for parties where they decorated with shamrocks and candles with green shades.

Mrs. J. E. Clark and her mother Mrs. Catherine Steward seated their guests at a long table that had small green ribbons running from the plates to the centerpiece. Attached to each ribbon was an envelope with a different verse of a familiar poem on the leaves of a broken shamrock, which were to be pieced together to complete the lines. (Graphic, March 24, 1910)

That same year, the domestic science class at the school held a dinner for their mothers who were very pleased that their daughters prepared it all at school during class. They served fruit cocktail, pigs in blankets, mashed potatoes with gravy, cabbage salad, olives and pickles, lemon pie, pineapple sherbet, cake and tea.

The Royal Neighbors (a women’s insurance group) played a game at their meeting where each member was blindfolded and given chalk to draw a pig on a blackboard. (The pig was one of the sacred animals of Ireland.) Then they were given a potato, tooth picks and paring knife to sculpt a pig. Mrs. King was the winner and was given her pig as the booby prize besides the blue ribbon. (Mercury, March 13, 1923)

If you have ever wondered when is the best time to plant potatoes, the following story from March 17, 1917 in the Graphic might answer your question.

“There were four men in town and they were arguing about when it was the best time to plant potatoes. One said March 17th on St Patrick’s Day was the one and only lucky day for planting. The next man argued that Good Friday was the only day to do the work. Naturalist No. 3 said wait for signs, the dark of the moon, etc., etc., etc. Arguer No. 4 disbelieved all the theories and said plant whenever you have the time and money to purchase the ‘spuds’. And the argument broke up and each man decided arguer #4 was right insofar as to bury the ‘spuds’ if you had the bankroll to purchase the seed.”

The last stanza of the traditional Irish folksong, “The Wearing of the Green” reflects the universal desire for freedom and homeland. This is very appropriate this year as we witness Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and show solidarity with their yellow and blue.

“Oh Ireland must we leave you driven by a tyrant’s hand

And seek a mother’s blessing from a strange and distant land

Where the cruel cross of England shall never more be seen

And in that land we’ll live and die still wearing Ireland’s green.”