by William F. Wolfgang, Phd

For several years, I’ve been searching through long-forgotten scraps of ephemera and old manuscripts for my upcoming book on Charles Edwards, Kinsley’s theatre director and impresario from the early 1900s. Recently, intriguing people and their fascinating stories have lodged themselves in my mind, and, perhaps, there’s no better year to share than Kinsley’s 150th Anniversary.

One example of this is Kinsley’s poet-author-composer-orator, Ila Carmichael Taylor. Despite the shadows of personal tragedy, Ila Taylor raised two children as a single mother while serving as a beacon for other women seeking careers before they even had the right to vote.

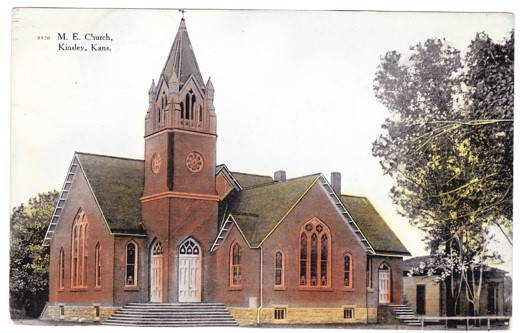

Ila was born in the small village of Washington, New Jersey, amid the Civil War in 1862. The seventh of eight children spread out across twenty-three years, she was always surrounded by family growing up. For the rest of her life, there would be nothing more important to her. Around the time she would have finished schooling at age sixteen, her brother Ed Taylor, eighteen years older than her, took his family west in search of the opportunity that eluded him. His destination was a small five-year-old town called Kinsley.

The young and creative Ila chose to stay behind in New Jersey, as there was still opportunity for her at home. Soon, she married Louis Hann, the First National Bank of Washington’s head cashier. Her new husband wasn’t just a cashier, however; he was also the son of the bank’s founder and a local judge. Ila had married well, or so she thought. After the birth of her daughter Louise and her son Augustus (“Gus” for short) in ’86 and ’88, respectively, in 1891, the Hanns’ marriage collided with hardship. The tiny village erupted into scandal. Rumor persisted that Mr. Hann had thrown his wife down a flight of stairs during an altercation. The papers further noted that he had “otherwise cruelly treated her.” As a result, Ila fled with her children to New York.

Seeking a divorce, Mr. Hann concocted a plan to frame Ila for infidelity, which would give him custody of their children. As Ila went about her daily business, her estranged husband had her “shadowed” by nefarious “private detectives” who were then to testify against her in court with maliciously fabricated lies.

The September 20, 1892 edition of the Jersey City News sensationalized the trial with articles like “Shadows on Wedlock: More Disgusting Testimony by the Detectives in the Hann Divorce Suit.” During their time on the witness stand, the “private detectives” proceeded to slander Ila’s character. Ultimately, the vindictive Mr. Hann and his cronies failed, and Ila received custody of the children.

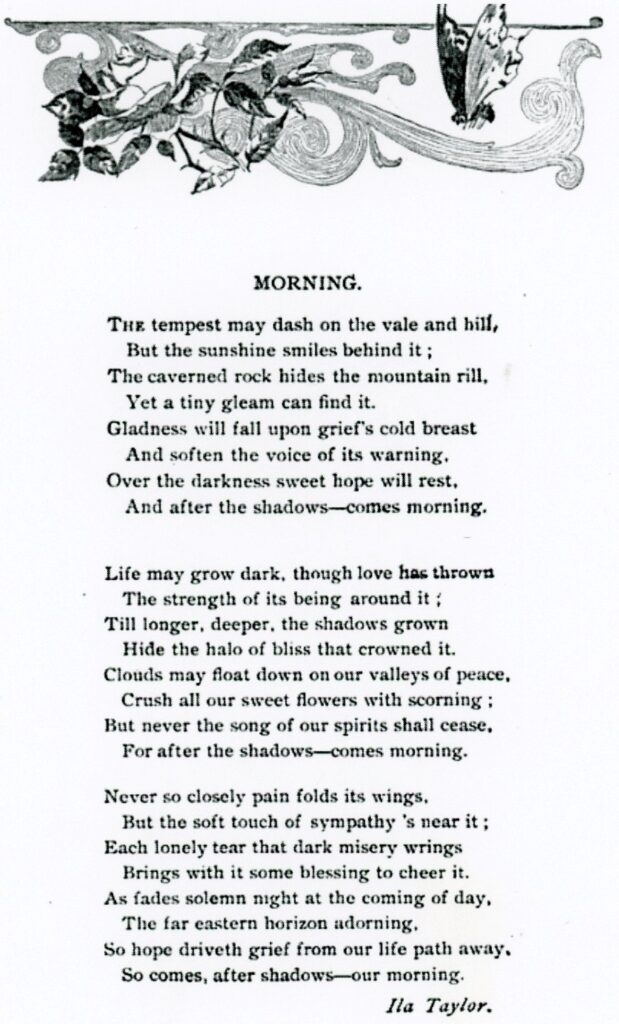

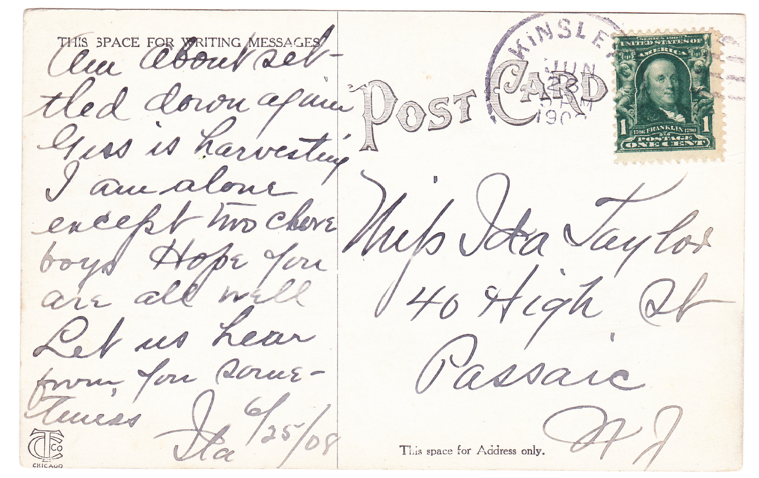

After the terribly public divorce proceedings covered in the smallest and largest papers, Ila penned a healing poem, which the popular Munsey’s Magazine published in February of 1894. She named her verse “Morning,” and lyrically described how each “coming of day” vanquishes the shadows, no matter how deep or long they may be. When her father passed away later that year, he had a line similar to this poem inscribed on his gravestone. Ila’s words served as his light even in death.

As the nineteenth century faded into the twentieth, more adversity awaited. Ila had more shadows to conquer. First, her estranged husband died of “softening of the brain.” Later, she lost her sister in a terrible accident and then, a year later, another brother passed away.

In 1900, Ila was living comfortably with her two children, presumably working in an editorial capacity with some of New York’s largest newspapers, as she would later tell her friend, Kinsley’s one-time newspaper editor Charles Edwards. In a few more years, her daughter Louise would be married and off to make her own home.

When 1906 arrived, Ila’s son Gus was now eighteen and had a keen interest in farming and carpentry. But to explore this, he needed a job and to escape his childhood in the bustling city. Ila’s brother Ed, who moved to Kansas nearly three decades earlier, had the answer: visit Kinsley. Mother and son stayed with their relatives on their homestead south of the Arkansas River and fell in love with the community. Then, they decided to permanently leave behind New Jersey and dark reminders of the past. (Part 2 next week on settling in the Sand Hills.)

A note on sources for this article in 3 parts: This article was composed based on accounts and documents found in Richardson’s The Great Next Year Country, Ancestry.com, the postcard in my personal collection, Ila Taylor’s file at the Kinsley Public Library, my research file on Charles Edwards, and Newspaper sources from Kansas, New Jersey, and Oklahoma.