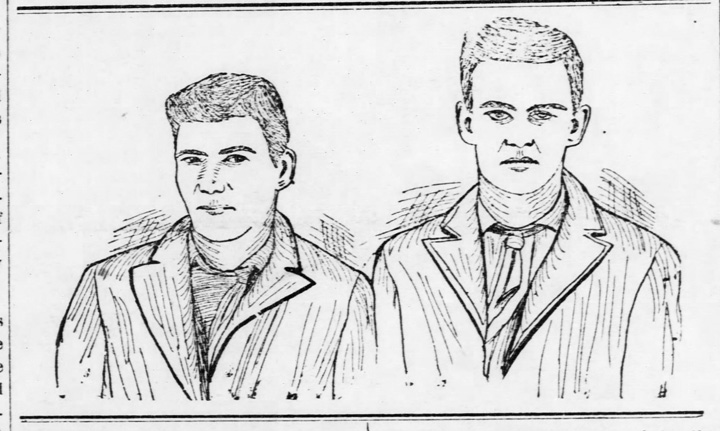

William Harvey, age 19, and Carl Arnold, age 17, were the two young men who murdered Kinsley’s mayor, John F. Marsh on Monday night, Oct. 22, 1894. Both boys had grown up in good families in Lane County and were living with their families in the Indian Territory (Oklahoma).

Inspired by reports of successful robberies, they went on a week-long crime spree. They stole two horses in Medicine Lodge, and held up a man and robbed a store in Wellsford. Then in a robbery attempt gone wrong, they shot and killed Marsh as described last week.

John Marsh was so respected, that had these men been caught that night, they probably would have been lynched. But they evaded capture and rode on to Lane County where they robbed a rancher of $40 and kept him tied up all day until they left.

They arrived in Russell Springs Friday night where they roused the suspicions of the county clerk and deputy sheriff who kept them under surveillance until a mob of eight men from Lane County arrived. Fearing that this mob might lynch them, they surprised the sleeping men and took them into custody.

On Sunday the prisoners were taken to Garden City. On Monday morning, a guard made up of Mrs. Marsh’s Bidwell relatives escorted them back to Kinsley on the 6:30 a.m. train. The Bidwells used “all their influence to prevent further lawlessness and by going upon the streets and asking their friends to see to it that the dignity of the law be maintained and no doubt preventing an attempt at lynching…. It was also the wish of Mrs. Marsh that the law be allowed to take its course.” (Tiller and Toiler, Nov. 9, 1894).

Justice moved faster in those days. On Nov. 13, 1894, Judge Vandivert convened district court in Kinsley one hour before the regular time in order to frustrate any would-be lynchers. Harvey and Arnold pled guilty, and Judge Vandivert sentenced them to hang with these words:

“I say to you now, candidly too, that so far as I am concerned you need never expect any help from me in the way of procuring executive clemency. I shall insist that you be executed, and that failing, as long as I live I shall insist that your punishment be continued, because you have murdered my friend and neighbor whom I have loved as a brother, and you have robbed this community of one of its best citizens.” (Graphic, Nov. 16, 1894)

The two were put on the 9 a.m. train and hurried to the penitentiary at Lansing.

At this time, Kansas law required that the condemned be kept in prison for one year, and then the governor had to issue a warrant to have the warden carry out the execution. But no Kansas governor had signed such a warrant under this law. Consequently, the death penalty had not been carried out, which may have been the intent of the lawmakers who originally passed the law.

After one year, Judge Vandivert, accompanied by E. T. Bidwell, visited the governor and formally demanded he carry out the execution. They presented a petition signed by 600 Edwards County Citizens. The governor agreed that if “any criminals ever needed hanging the Kinsley murderers did, yet as no governor had ever signed a death warrant, he would not establish a precedent for capital punishment.”

Then Edwards County Attorney A. C. Dyer demanded to have the prisoners returned to Kinsley to have the sentence carried out. When this was refused, Dyer brought an action in the Kansas Supreme Court which ruled “that no court has the power to fix a time for the execution of a death-sentence before the governor has named a day for carrying it into effect….” Arnold and Harvey now faced life in prison.

In 1901, Arnold’s lawyers and his mother petitioned Governor Stanley to pardon Carl because he was so young at the time of the crime and had not intended to kill Mayor Marsh. Without even allowing the Graphic editor, James M. Lewis, to present a protest document signed by nearly everyone in Kinsley, the governor denied the pardon request.

Wood inlaid table made in Lansing Penitentiary by William Payne Harvey and given to Governor Stanley around 1900. (Kansas Historical Society Collection)

In 1907, the death penalty was abolished in Kansas, and Governor Hoch became aware of a book, “Kansas Inferno,” and a poem that Carl Arnold had written. After meeting him in prison, he decided to commute both his and Harvey’s life sentences to eighteen years. They were released in May, 1909. It is not known what became of them.

No one was hanged in Kansas from August, 1870 to March, 1940. The death penalty was reinstated in 1935 when it could be imposed by juries. Among the fifteen executed from 1944 until it was ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1972 were Richard Hickock and Perry Smith who murdered the Clutter family in Holcomb. They were hung on April 14, 1965 in the Lansing facility. Two more famous murderers, George York and James Latham, were hung on June 22, 1965 after their cross-country killing spree. These were the last executions in Kansas despite Kansas being the last state to reinstate the death penalty in 1994.