I ended up last week’s article with Leah Williams graduating as valedictorian from Kinsley High School in 1918. WWI was still raging in Europe and the Spanish Flu had struck.

In August Leah found employment as a relief telephone operator in Lewis. Then on an ideal evening in late October, she joined some of her friends for what was probably a going-away party at the river with a bonfire and lots of food. The next week, she and her sister Juanita left for Lawrence Business College. We might assume that the cash scholarship Leah had received from a local club at graduation was applied to her tuition.

Over the next year, Leah received secretarial training and held down three part-time jobs and a night job in Lawrence. One job was in a large hardware store which sold art supplies. She enjoyed helping to arrange store displays there.

Maybe she got run down from working too hard, but sometime in 1919 she contracted tuberculosis. Before antibiotics, the treatment in those days was to go to the state sanatorium in Norton, Kansas for complete rest. She would be a patient there for over a year, from March 1920 until May 1921.

I learned something interesting about healthcare for the poor at this time. The Board of Edwards County Commissioners’ POOR BILLS were published each month in the Kinsley Graphic. One item regularly listed was “State Sanatorium, care of Leah Williams”. Each month, an amount of about $1 a day was paid for Leah’s care.

Leah’s only complaint against the hospital was that they would not permit her to do anything which made her days very long. She enrolled in a correspondence class in lettering to help alleviate her boredom. That would be the beginning of her desire for a career in art.

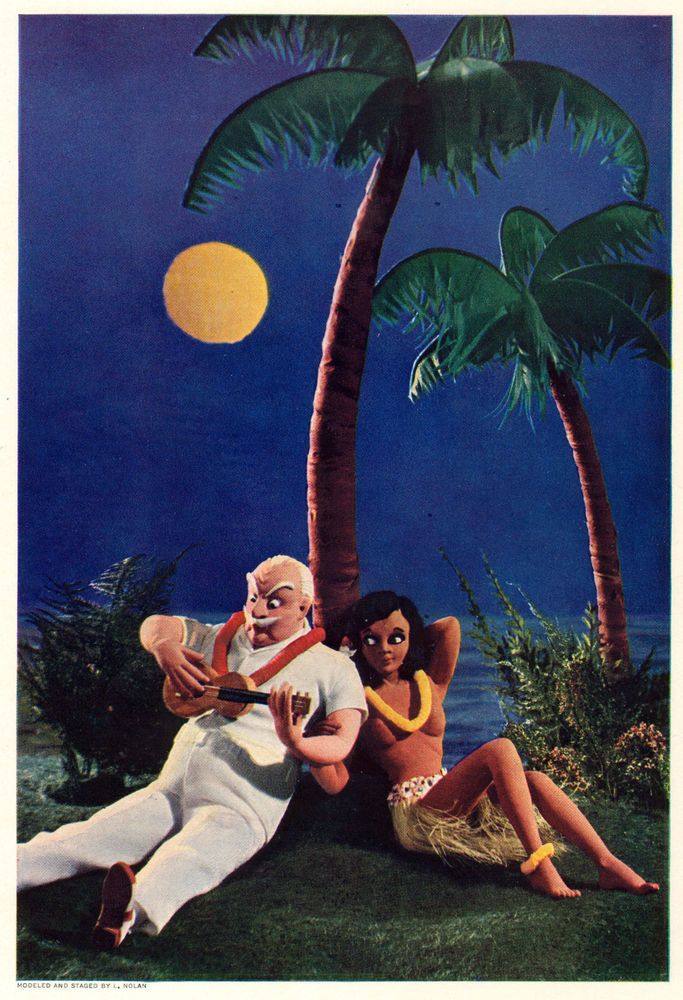

She finally made a good recovery and moved to Denver, Colorado where she enrolled in a course in poster art. She began making advertising placards and displays for windows and lobbies in stores and theaters. She also began experimenting in constructing small figures for table favors patterning them after people she saw.These small sculptures had a wire armature covered with cotton and wrapped in crepe paper. They were very detailed and intricate dolls right down to pin-head sized fingernails, eyes, and lips all cut from crepe paper and glued on.

Leah continued developing this technique, and by 1925, she was working with photographers to use her figures in settings for cartoons and illustrations. The figures were often of actors and displayed in theaters in Denver. Many actors of the time, including Fanny Brice, gave her commissions to make them.

According to the 1930 census, Leah had married William J. Nolan, a dry goods salesman in 1924. I could not discover anything else about their marriage except the 1940 census listed Leah as divorced and living in a boarding house in Chicago. She had moved to Chicago in 1933. She did keep the Nolan name for her professional career.

One interesting question that the 1930 census asked was if the household had a radio set. The Nolans indicated they did not.

In Chicago, Leah made figures for cartoon illustrations photographed for Esquire Magazine, Look Magazine, Saturday Evening Post and Coronet Magazine. Then she gave up this commercial work to study painting at the School of Design with Hungarian artist Lazio Moholy-Nagy.

December 1, 1935 with the caption, “I’ll master this ukulele if it takes all night”.

In 1941, in support of the military’s need for draftsmen during WWII, Leah took a 3-month concentrated course in engineering drafting at Illinois Institute of Technology. Afterwards she taught there for two years before becoming a civilian engineer at the Palm Spring Army Air Force Base.

After the war Leah went to Stratford, Connecticut and then on to New York City in 1950 where she alternated her career in painting and exhibiting with commercial drafting. In 1967 she retired from drafting and devoted full-time to painting and exhibiting in galleries and museums in Michigan, New York, Connecticut, and other places. She experimented with new ideas and techniques in her painting, figure construction, and even video.

Leah Williams Nolan returned to Kansas where she died in Wichita on January 6, 1982 at the age of 80. She is buried in Hillside Cemetery. Her papers are archived in the Kenneth Spencer Research Library at KU and the Kinsley Library owns one of her paintings.

Leah Nolan had an artist’s eye for observation. During our fairy tale summer reading program, we asked the kids to look closely at face cards to see the differences in the jacks, queens, and kings of different suits. You probably know about one-eyed jacks, but there are many other differences. Leah Nolan and Ross Parmeter noted them in his book, The Awakened Eye. I have been playing cards all of my life, but if you’re like me, you’ll find that you never really looked at those face cards. Click here to discover what you have never noticed.

Leah Williams Nolan picture from Louise Wire’s scrapbook.

Leah Nolan’s crepe paper figures photographed for an illustration in Esquire magazine, December 1, 1935 with the caption, “I’ll master this ukulele if it takes all night”.