Last week you read about the new AT&SF railroad bringing settlers to Kinsley in 1873. During my research into train-riding at that time, I came across “The Diary of a Dodge City Buffalo Hunter, 1872-1873” in the 1965 Winter issue of the “Kansas Quarterly”.

On Nov. 16, 1872, Henry H. Raymond rode the train to Dodge City to hunt buffalo with his brother Theodore. Six days later the brothers, along with Bat Masterson and Abe Mayhue, were out on the prairie hunting and skinning buffalo. Over the next nine days, by Dec. 1, these men killed 116 buffalo. The diary continues to describe a year of hunting and living life on the prairie.

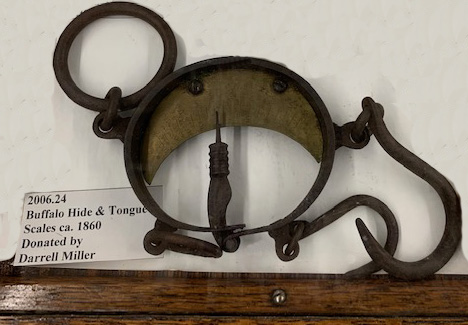

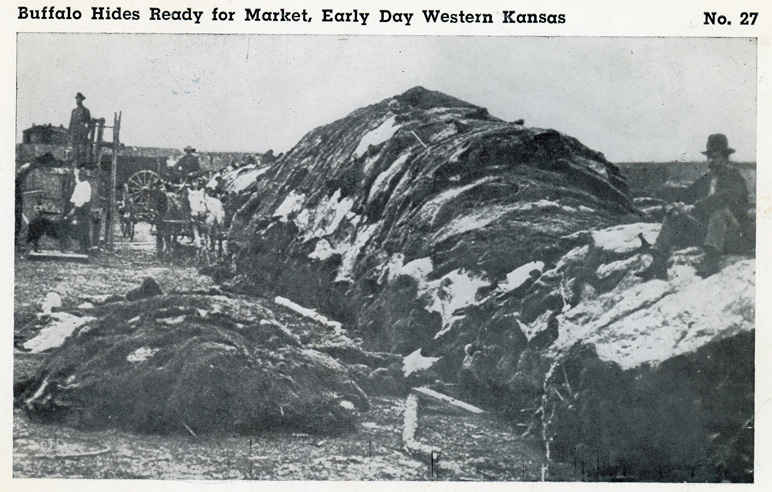

From 1869 to 1884, the bison population went from 30 million animals to only 325. The government had encouraged the slaughter because “Every buffalo dead is an Indian gone.” The carcasses were left to rot, with only the tongues and hides harvested. The transcontinental railroads had made it economically feasible to ship hides for robes and machinery belts. Goods and settlers came west on the train; then on the return trip, buffalo robes, and later bones, were freighted east.

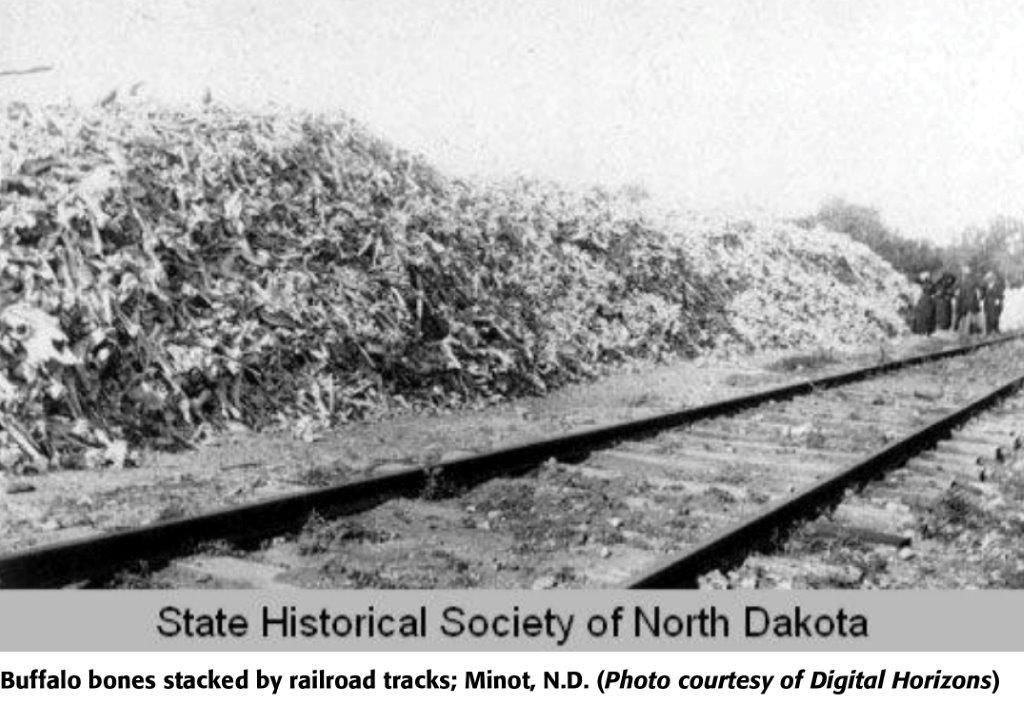

Settlers in Kinsley in 1873 were able to find and hunt buffalo for meat when they first came. However, that did not last long with the extermination of the herds. Bison bones were valuable as they were used in refining sugar, making fine bone china, and most importantly, manufacturing fertilizer. Bones were scattered across the prairie, and a settler could supplement his income by picking them up and selling them in town.

Kinsley became a place to drop off and ship buffalo bones. In 1877, the Edwards Bros. & Price had a store at 125 E. Sixth St. (Circle K). They sold just about everything, and they bought buffalo bones for $5 a ton. These were brought in from as far away as Coldwater and left in piles by the railroad tracks. It is estimated that it took 100 animals to make a ton of bones.

That brings us to 1878. Kinsley had grown but it was not yet a legal city. Today cities pass laws to control nuisances like loose dogs, junk cars, and weeds. In 1878 one reason that towns became incorporated cities was to control nuisances. The following sarcastic remark describes some 1878 nusances.

“Swine rooting in the highways of business, piles of buffalo bones and decayed carcasses stretched in front of the principal thoroughfare, men tearing through town on horseback, howling like live Comanche Indians, and sometimes making day and night hideous with their discord, to say nothing of danger to citizens from promiscuous shooting of revolvers – oh, no, there is no need of an incorporation.” (The Valley Republican, June 22, 1878)

That summer, several wagon-loads of buffalo bones arrived daily from the range. The piles of buffalo bones were deemed a health hazard by the citizens and physicians. At a town meeting that September, “Mr. Blanchard stated that scarcely a family in the north part of town was free from sickness, owing to the effluvia from heaps of bones piled along the railroad track…. He hoped that the people who maintained such a nuisance as the piles of bones had become, might be made to feel the weight of public sentiment.”

The owner of the bones, Mr. R. E. Edwards “…did not believe the bones were injurious to health. They might be a nuisance to be sure, but he didn’t want to stop the bone trade…. He came here to do business and make money. Lots of things don’t look pretty, but beautifying a town was unprofitable.”

Mr. Edwards did agree to move the pile if the city paid a night watchman to guard them. Despite his objections to incorporation which he thought would raise taxes, Kinsley did incorporate on November 12, 1878.

In May, 1879 A. B. Hopkins of St. Louis purchased 300 tons of buffalo bones. The editor of the Valley Republican wrote, “We are glad to have the old eye-sore, that pile of bones, removed from our side track, and as the council have passed an ordinance prohibiting the unloading of bones within the city limits, except at the stock yards, we will no longer be annoyed by that nuisance.” (Valley Republican, May 24,1879.

The paper reported a year later on Nov. 22, 1879. “some ten cars of buffalo bones are piled up just east of J. Q. Moulton’s residence, waiting shipment.” Moulton live in the triangle lot between First and Second St. on the northside of Hwy 56. East of his house, probably got the bones outside of the city.

In March, 1880, between 100 and 200 tons of buffalo bones were piled up just east of town. And in July 1880, “Loading and shipping buffalo bones has been the chief attraction at the depot this week.”

That seems to have marked the end of bone shipments out of Kinsley. The ordinance was passed just before it was no longer needed. The buffalo were gone.

(Donated to Edwards County Historical Society Museum by Jason Arensman)