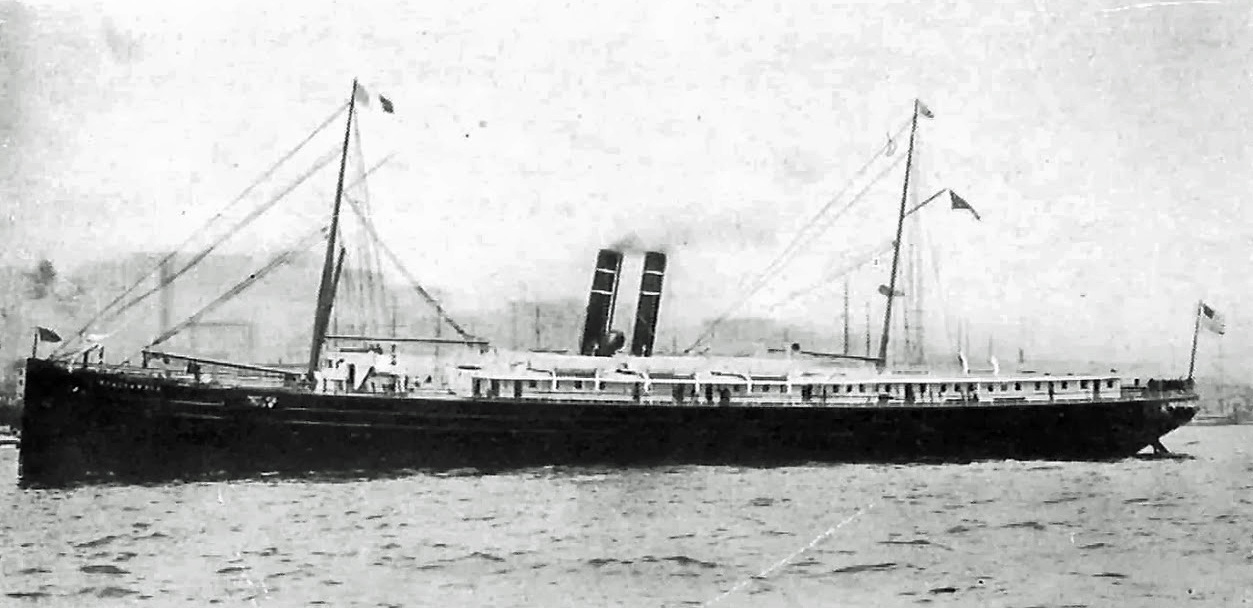

“The American Ship Vigilancia, sunk by a German submarine, occupied a warm spot it the hearts of Kansas negroes. It was the ship that carried the Kansas negro troops to Cuba during the Spanish-American War.” (Kinsley Mercury, March 29, 1917)

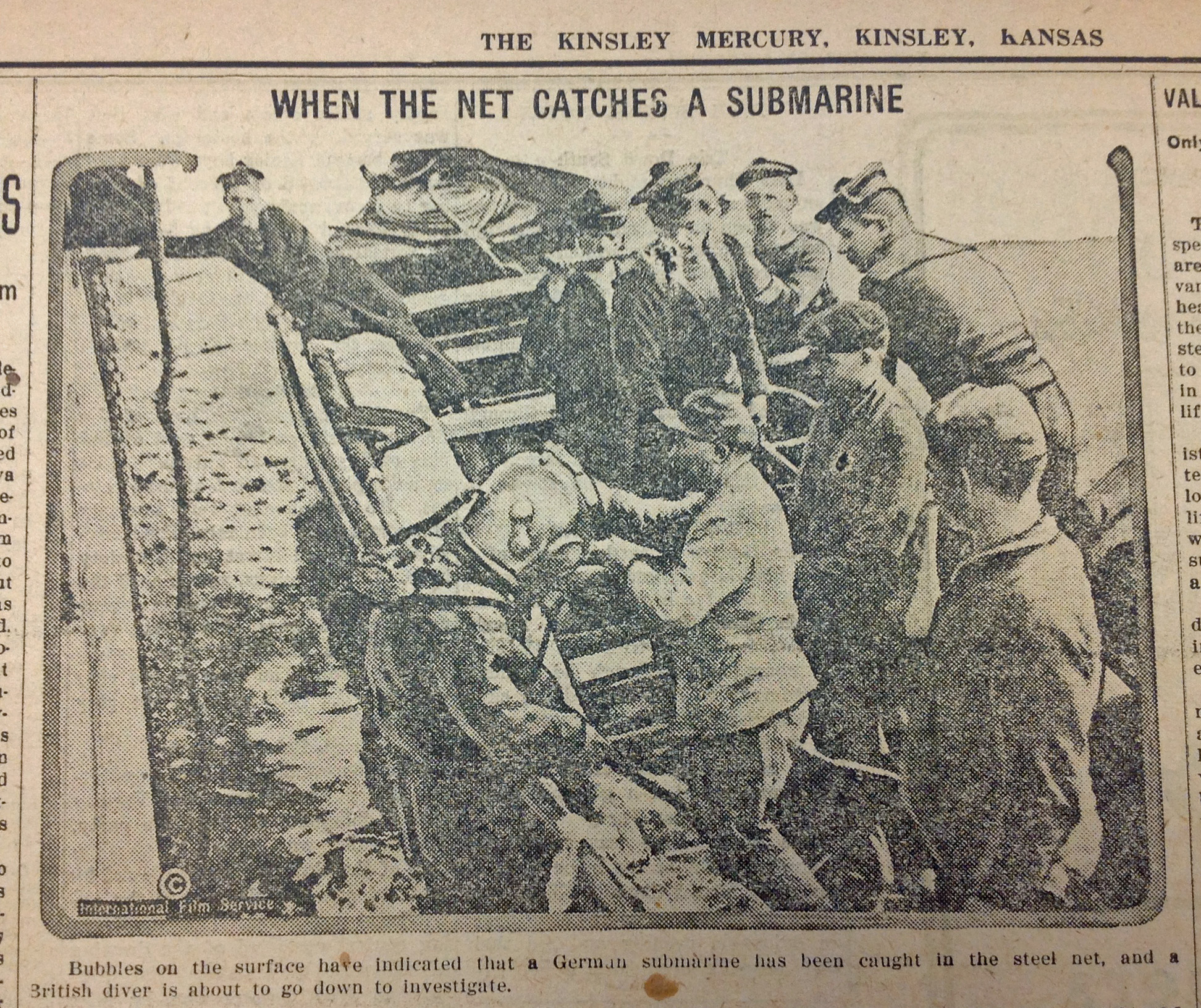

This brief mention of the Vigilancia in the Mercury tells about the dangers German submarines brought to the Atlantic. Despite the fact that the Vigilancia was flying the American flag and had the name of the ship and the flag painted on both sides, it was torpedoed on March 16, 1917, 145 miles west of the Scilly Islands, Great Britain on its way back to New York.

Vigilancia’s Captain, Frank A. Middleton, reported that the ship was attacked without warning at 10 a.m. Friday morning. Two torpedoes were fired. The first one went astern and missed the ship, but the second one hit the starboard side. It took no more than 10 minutes for the ship to founder.

Two lifeboats were lowered from the Vigilancia and the crew of 43 men got into them. Owing to the swell of the ocean, however, 25 men were thrown into the water. Ten were able to be picked up by the lifeboats, but the other 15 men were drowned.

“After rescuing as many of the crew as possible in the boats,” reported Captain Middleton, “we had biscuits and water. At night I fired distress signals. Several times, by the glare of the lights, I saw a submarine following fifty yards from the boats between 10 o’clock Friday night and 2:30 o’clock Saturday morning, but it made no attempt to help us. We suffered great hardships in the boats. One man of the engine room staff is paralyzed as a result of exposure.” (Chicago Tribune, March 19, 1917)

The survivors remained in the lifeboats from Friday morning until Sunday afternoon before being picked up and taken to the Scilly Islands.

During the month of March, four other American ships were sunk (Algonguin, City of Memphis, Illinois, and Healdton). American ships began arming themselves for protection. President Wilson contemplated calling for an immediate session of Congress to ask for authority to adopt aggressive measures including sending warships with orders to seek out submarines to clear the trans-Atlantic lanes. The country was getting closer to declaring war.

Before leaving this post, I want to go back to the quote from the Kinsley Mercury regarding the all-black 23rd Kansas Volunteer Infantry during the earlier Spanish-American War. The 23rd was commanded by Lt. Col. James Beck and led by other black officers. This was unique at a time when white officers normally were in charge.

The 23rd left Topeka on August 22, 1898 for New York City and on August 25 sailed for Cuba on the Vigilancia. It was a stormy and uncomfortable voyage, but they arrived in San Luis, Cuba where they took up occupation duties of guarding Spanish prisoners of war from guerrilla bands and later helping to build roads, bridges, and improve sanitation.

These citizen-soldiers ate poorly with meals of rancid bacon and coal oil damaged wheat. They had no fresh meat until December. Still, they were better off than the inhabitants who were starving. They were also plagued with malaria, typhoid and dysentery. Despite these conditions, “Excellent discipline was maintained and all duties were cheerfully and faithfully performed.” They came back to Fort Leavenworth on March 6, 1899. (This information was gleaned from The Black Citizen-Soldiers of Kansas, 1864-1901, by Horace Leonard Baker and Roger D. Cunningham.