It is way past time to get this World War I blog going again. I thought I would be back at it after summer reading ended, but it seems like we have been busier than ever since then. Now our “World War I and America” discussion series is rapidly approaching. December is a quieter month at the library, so I hope to again delve into the local 1917 papers. I’ll also try to catch up on the war news of 100 years ago that I missed up until now.

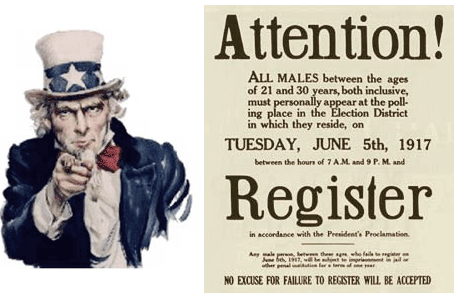

On June 5, 1917, men, aged 21-31, were required to register for the draft. 708 men registered in Edwards County by filling out a card. (Interestingly, only about 300 men in that age group live in the county today.)

J. M. Lewis, editor of the Kinsley Graphic wrote in the June 7 edition: “Registration day was very quietly observed in this county. Those who were eligible attended to the duty without any objection whatever, feeling that they were doing their patriotic duty….Each man who registered was presented with a flag pin through the kindness of Mr. J. S. Craft who supplied the registration places with them for presentation.”

That month, a local draft board was named and consisted of Sheriff G. D. Hoffman, County Clerk Florene Erwin, and Dr. L.M. Schrader. The board numbered the completed registration cards in red ink from 1 up to the total number of men registering. Men could learn their red number at the board, and the names and numbers were also published in the local newspaper.

Selection was done by drawing numbers in Washington D.C. For example, if Number 10 was drawn in Washington, then whoever was Number 10 in Edwards County would know he was being selected by the draft. There were about 30,000 draft districts in the country, so when Number 10 was drawn, 30,000 men were being selected, one from each district. By keeping the printed list of men with their numbers registered in Edwards County, everyone could tell at once who had been selected as soon as Washington announced the numbers.

All men notified of selection were required to go for a physical examination. Men had seven days from their notification letter to file for an exemption or discharge. Those who were exempted included: United States officer, legislative, executive, or judicial; ordained minister or in seminary on May 18, 1917; already in the U.S. military service; a German subject or resident alien. Local boards could also exempt a man if he were: a county or city officer; a customhouse or postal employee; working in an armory, arsenal, or navy yard; a licensed pilot or mariner working as such; married or the sole support of dependent children or parents; or a member of a pacifist religion.

On July 26, the list of the first 105 numbers selected for the draft was published. Forty-one of these men were single and immediately eligible. Of those, thirty-one would be inducted. Nine were from Kinsley, eleven from Lewis, and the rest from nine other small towns. Twenty-three of these men would be inducted into the army by October 7, 2017. Eight others would not be inducted until 1918. War had come to Edwards County.