Usually at this time, I am vacationing in my native Michigan where it is 75° and the Great Lake shimmers a beautiful blue. However, this year, Covid-19 has kept me suffering the heat and damaging storms in Kansas. But as I pondered a topic for this week, I found myself virtually traveling to a different place and back in time.

This story starts in 1798 when construction began of the finest mansion on the Tennessee frontier and located at Gallatin, Tenn., just NE of Nashville. The owner of this plantation fought in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, battled indigenous Indians, and helped to co-found Memphis. He named his new home Cragfont, as it stood on a rocky bluff above a cool spring.

The plantation was only made possible by the labor of more than 100 African-American slaves who lived in row quarters on the property. They grew the cotton and tobacco that supported the lavish lifestyle of the plantation.

The owner died in 1826 and his wife carried on with help from her youngest son and some of her other 11 children.

In 1847, a baby boy, Albert, was born in the slave quarters. In 1860 we know that twenty-five slaves were divided by age between 3 of those 12 children. Helen received Albert along with 7 other male slaves and 2 females ranging in ages from 12-24 years old.

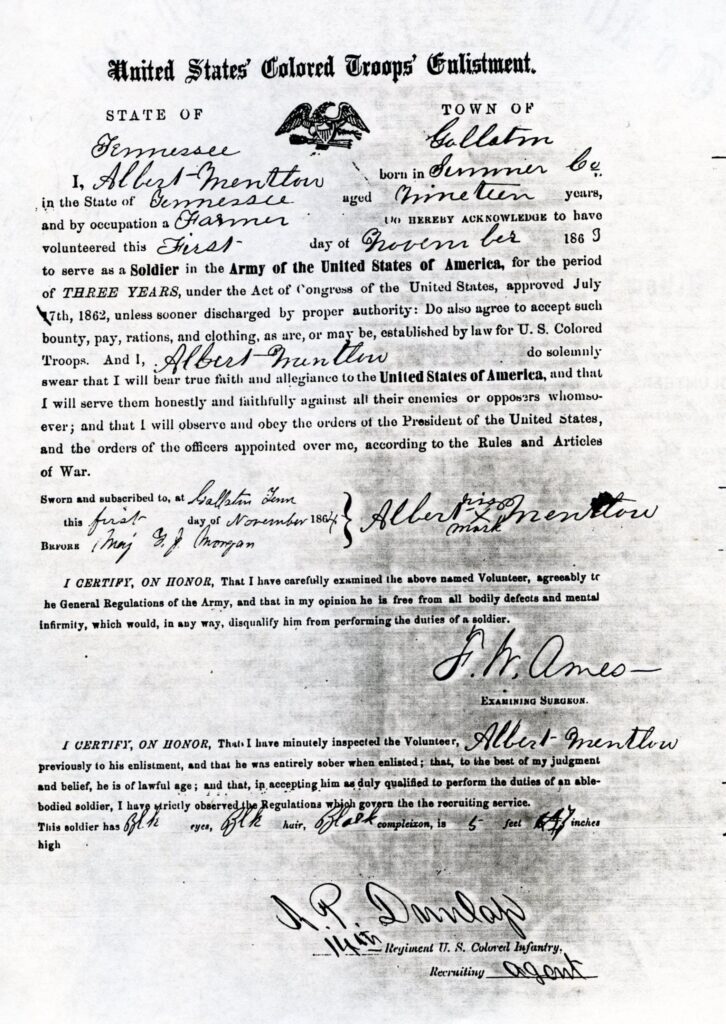

In November of 1863, Albert left the plantation and enlisted in Company B, 14 United States Colored Infantry. He used the name or Albert Menthow. His real last name was that of his plantation owner, but to protect himself, he changed it to Menthow. When the war ended at Appomattox in April, 1865, Albert would change his name back to his original slave owner’s name of Winchester. He continued to serve out his 3-year enlistment until March 26, 1866.

Some of you are now beginning to understand the Kinsley connection. I’m not sure what Albert Winchester did for the next twenty years, but in 1884 he joined the Exodusters and came to the “Promise Land” of Morton City, just east of Jetmore. We can imagine he got off the train here in Kinsley and walked or rode in a wagon on that early trail described in #5 of this blog..

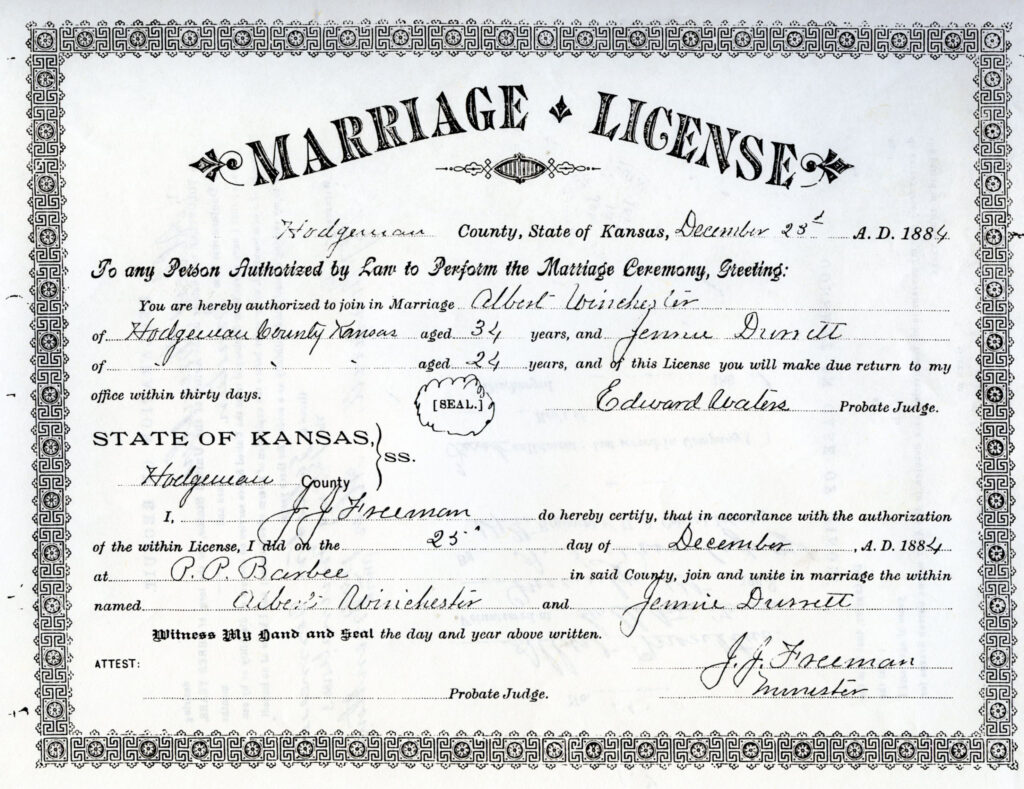

That first year, Albert met Jennie Durnet, and they were married on Christmas Day, 1884. The officiating minister was J. J. Freeman, who unlike Albert, did not choose to retain the name of his slave master. Jennie was 24 years old and the first five of their ten children were born in Hodgeman County.

They moved to Kinsley where five more children were born . The Winchesters bought 40 acres of land just west of Kinsley’s city limits for $260 on May 15, 1897. They were respected members of the community. All their children would move away from Kinsley except John, better known as Skeet, who married Lenora Walker, and they had nine children.

Albert Winchester was granted an original Civil War pension of $8 per month in December of 1899. He died on June 3, 1900 and is buried at Hillside Cemetery in the row of Civil War veterans who had fought to end slavery. His grave is closest to the Civil War Memorial.

Albert was highly respected during his lifetime and equally honored every year after his death with the traditional Memorial Day gun salute. In 1971, the avenue on the western edge of town where the Winchester family had lived for three-quarters of a century was renamed in honor of Albert Winchester and his family.

Albert died in 1900, so it would be left to his son Skeet to witness the emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in Edwards County in 1923, and to his grandchildren who could only sit in the balcony of the Palace Theater, and to his great grandchild, Kenny Gaines who would become a lawyer and join the fight for civil rights in the 1970s.

If you’d like to learn a little more about the Winchester family, access the online oral histories of Norma Kennedy and Kenny Gaines in the library oral history collection. https://kinsleylibrary.info/patterns-of-change/patterns-of-change-interviewees/