If you are of a certain age, you probably have a small scar on your upper arm. It is barely noticeable, but if you are like me, you remember how you got it. I was five years old and had to get a smallpox vaccination in order to go to school.

My vaccination came to mind when I was reading the Dec. 8, 1921 issue of the Kinsley Graphic. It reported an outbreak of smallpox exactly one hundred years ago in the fall of 1921 in Kansas City.

Smallpox was a terrible disease. About 3 out of every 10 people who got it died. People who survived often had severe scarring. Smallpox was spread through coughing and sneezing or sometimes through contaminated clothing or bedding.

By 1921, smallpox was not as common because in 1796, the English doctor Edward Jenner developed a vaccine from cowpox that protected a person from smallpox. At the time, he dreamed of the day that “the annihilation of the smallpox, the most dreadful scourge of the human species, would be the final result of this practice.”

The smallpox vaccine was given using a special two-prong (later 5-prong) needle and instead of puncturing the skin once, multiple punctures delivered the vaccine just below the epidermis, usually leaving a small round scar.

It does not appear that Kinsley ever had a severe outbreak of smallpox, but occasional cases did occur. Ray Wetzel told me that some of those buried in Kinsley’s first cemetery (1878-1886) died of smallpox.

The Dec. 1, 1893 issue of the Graphic wondered why smallpox cases still existed when the vaccine was available. The paradoxical answer given was because the vaccination was so successful.

“So nearly has it banished small-pox that no one now fears that disease, and a general carelessness prevails regarding it.” Simply put, people had forgotten how deadly it could be and were not getting vaccinated.

From 1899 to 1904, there were 164,283 confirmed cases in the U.S, and some thought the number was five times that high. Vaccinations were then mandated and a certificate was required to go to work, attend school, ride on trains, and go to the theater. To thwart those who forged a certificate, they were required to show their vaccination scar.

In March, 1905. Dr. Charles Mosher suspected two cases in Kinsley and asked Dr. Samuel J. Crumbine to come to Kinsley to confirm. Dr. Crumbine was the Kansas Secretary of the State Board of Health and is well-known for his “Don’t Spit on the Sidewalk” bricks to help curb tuberculosis. Dr. Crumbine arrived and determined that Frank Heath and Powell Class did have a mild form of small pox.

Mosher Drug Store, 124 E. Sixth St. (currently Twice is Nice)

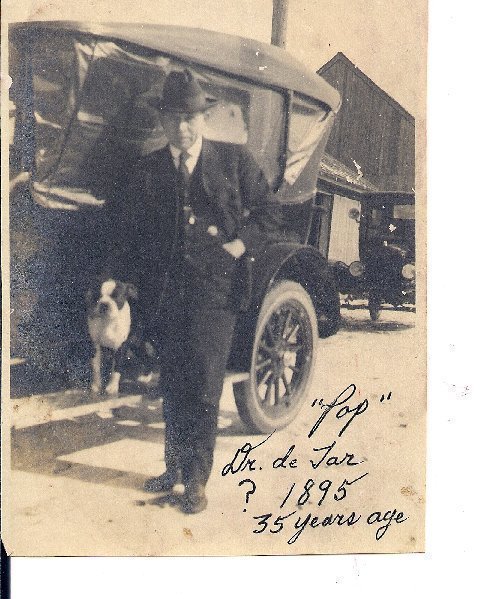

Dr. I. M. DeTar. Edwards County Health officer at the time, ordered a strict quarantine. He wrote in the Graphic that, “while the disease is here in a modified form, yet none of us want it, and the way to insure it not spreading is to observe the quarantine direction closely.”

With the vaccine readily available, there was no reason to have had the 1921 Kansas City outbreak which caused 271 cases and 96 deaths. By December it had spread to Topeka, Wichita, Hutchinson, Dodge City and other Kansas towns.

Dr. DeTar approached the school board and “In order to protect our community from an epidemic of this disease, it was decided to commence next Monday the vaccination of school children. The Board of Education will furnish the vaccine, and the doctors of the city will give their services free, so there will be no expense to the children.” (Graphic, Dec. 8, 1921)

A world-wide effort to eradicate smallpox was undertaken after World War II. Through widespread administration of the smallpox vaccine, Dr. Jenner’s dream was finally realized when the smallpox virus was declared “extinct” in the U.S. in 1952. Routine vaccination for smallpox was stopped in 1972 and the scar no longer appeared on children’s arms.

The World Health Assembly declared the world free of smallpox in 1980. Many people consider smallpox eradication to be the biggest achievement in international public health.