As mentioned in last week’s article, January 1, 1886 was a mild day. The afternoon became misty, with rain that turned into snow that evening and rapidly grew worse. By midnight a blizzard was in full rage. The people of Kinsley managed to dig out and survive with a supply of coal and food. Rural residents were not as fortunate.

Some settlers on the prairie lived in loosely constructed board shanties. The only insulation against the wind and cold was often newspaper on the walls. Others lived in a lowly dugout which was actually more comfortable. They were protected from the wind, and snow was an insulator.

For many days it was a struggle on the prairie to find fuel to burn to keep warm. Some resorted to burning their furniture or would dampen hay to make it burn more slowly.

About 30 people died in western Kansas, but I could not discover that any of them were in Edwards County. Men, women and children died by getting caught and/or lost in the storm. Farmers were spared by stringing a rope-line to the barn. Both the Graphic and Mercury did write of many bad cases of frozen hands and feet in the hills south of Kinsley.

D. L. Simmons who lived between Dodge City and Spearville, wrote the following remembrance in the Wichita Beacon (January 22, 1922).

“When daylight came, the air was white. It was like looking against a sheet. There was not a minute of the day that you could have distinguished a cow from an elephant one rod from your door.

“I had a good barn about a hundred yards from my house, with six horses and twelve cows and calves in it. The snow came through cracks around the doors until the horses’ backs were against the top. The blizzard continued until midnight. On the morning of the third day, it was drifted level with the top of the barn. I was two days getting my stock out of the barn.

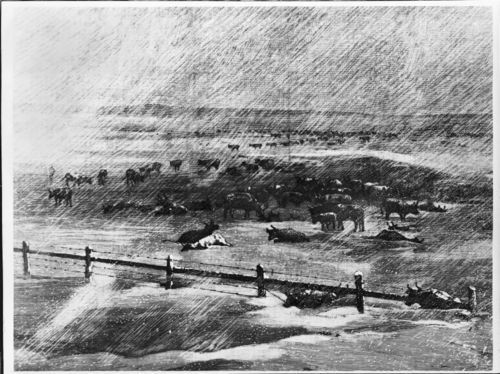

“Almost everything, man or beast, that had been out during the blizzard died. There were 1,500 head of cattle killed on the Arkansas River between Dodge City and Kinsley….Many of the frozen cattle were skinned and saved for meat.”

On January 16, 1886 the Dodge City Globe reported that the below-freezing north wind caused the cattle to drift south “…until they came to the river, and rather than stand there they attempted to cross and perished instead. Some by breaking through the slush and ice, and others by falling on the ice and being unable to get up.”

“According to a news item, a bachelor spent the storm in his 10-by-12 foot shack on a plot of land in Edwards County. But he was not lonely during the raging blizzard. Sharing his house were two bachelor friends, his dog, nine head of cattle, three hogs, 18 chickens and one horse. Under these conditions the motley assortment of creatures endured two days and two nights. If misery loves company, surely this fellow must have felt great gratification.” (Hutchinson News, Jan. 1, 1986)

In Fellsburg, Mr. John Reeder lost five head of cattle in the storm. Mr. Fell lost eighteen head of hogs, and Mr. L. White had eight head of hogs to smother in the snow.

The Kinsley Mercury (February 20, 1986) told a very different story of Hugh Bartis Oliphant’s hog. “The place where the animal had been in the habit of bedding at night was covered by a huge drift, and after prodding around in the snow for a while without finding the porker, Mr. O. concluded that he was lost bacon and gave the search up.

“Five weeks after the animal disappeared, the melting snow disclosed the emaciated form of the hog still alive and kicking. Mr. Oliphant says the animal presented a pitiful spectacle when first uncovered, being crazed for food. It bit and snapped at everything within its reach. Food was promptly place before the resurrected one and it is now fattening up rapidly.”

Some wondered if this story was true, but Mr. Oliphant stood by it.

Within days of the storm ending, the Graphic understated the disaster and voiced the spirit of the persistent, courageous, and ever hopeful farmer. “The new year opens up a little cold but the prospects for a good season were never more favorable than now. The wheat crop in western Kansas was never more promising that at this time. The fields being protected by a good fall of snow which remains on the ground and prevents from freezing.”